Wonder Woman, the epic block buster film of 2017, is a feast of visual delights, heroic battles, and Amazons1. As the narrative unfolds, we quickly learn that the young Diana, “Wonder Woman”, is no ordinary Amazon. As Diana is a god, her superhero feats are not surprising, but even the rank and file Amazons of Wonder Woman’s Themiscyra live up to their ancient reputation of being smarter, better, and faster than (non-Greek) men, as the ancient Greek orator Lysias (2.4, ed. Hude) noted2:

The Amazons were the daughters of Ares in ancient times who lived beside the River Thermodon. They alone of those dwelling around them were armed with iron, and they were the first of all peoples to ride horses, and, on account of the inexperience of their enemies, they overtook by capture those who fled, or left behind those who pursued. They were esteemed more as men on account of their courage than as women on account of their nature [phusis]. They were thought to excel men more in spirit than they were thought to be inferior due to their bodies3.

In ancient Greek lore, Amazons fought like other mortals, even though they were called the “daughters of Ares”, the god of war4. And while they are represented as brave, Lysias asserts that they were successful, in part, due to the inexperience of their foes. Yet, like the Spartans, the Amazons of ancient Greek legend seemingly existed to make war, whereas their counterparts in the Wonder Woman film have been put on earth by Zeus for a different purpose: to bring peace by defending all that is good in the world. In fact, rather than being the “daughters of Ares”, they are Ares’ sworn enemies.

As the movie begins to unfold, the viewer is treated to Hollywood’s vision of Themiscyra, the fabled homeland of the Amazons5. Themiscyra is not depicted as a settlement in northern Asia Minor, as is the case in Greek authors, but rather as the chief settlement of “Paradise Island”, replete with lush landscapes, waterfalls, and battle-training for women only. Although it was not the site of Themiscyra, Apollonius of Rhodes does mention an “island of Ares” off the coast of Themiscyra that was frequented by the Amazons. According to Apollonius, the Argonauts were warned about this island by the seer Phineus, who told them to

...beach your ship on a smooth island,

Once you have driven out with all sorts of methods the ruthless birds,

Who truly in countless numbers frequent the deserted island.

There the Amazon queens Otrere and Antiope erected a stone temple to Ares when they went to war (Apollonius of Rhodes Argonautica 2.382-387, ed. Fränkel).

The birds, like the Amazons, were sacred to Ares and commanded by him. In another passage, Apollonius gives further details of this island, describing a sacred black rock that the Amazons came to worship6. Once the Argonauts arrive at this “island of Ares” they encounter the sacred precinct erected by the Amazons:

They all assembled there between the pillars of the temple of Ares,

In order to sacrifice sheep. They hurriedly gathered around the altar, which was outside the roofless temple and was made of pebbles. Inside a black stone, which was sacred, and to which all of the Amazons used to pray, stood firmly fixed (Apollonius of Rhodes Argonautica 2.1169-1173, ed. Fränkel).

In contrast to having a black stone sacred to Ares, Paradise Island in Wonder Woman has its antithesis: “the godkiller” a sword inscribed in “Amazonian script”, intended to kill none other than Ares. The godkiller is reminiscent of the Sword used by Beowulf (1687-98) to kill Grendel, which was inscribed with Runes, except that the inscription is mostly in archaic Greek lettering7. Furthermore, the alleged godkiller is stored in a shrine of sorts, one which, like the sword itself, resembles a medieval fortress more so than an ancient Greek temple. Indeed, it was modeled on the 13th century Castel del Monte in Apulia, Italy8.

The godkiller is purportedly to be used to defeat Ares, the god of war, and the sworn enemy of the Amazons. Thus the Amazons, though they train constantly for war, have a paradoxical mission: to bring peace. Yet, despite their altruistic, feminist mission, the Amazons of Wonder Woman became the subject of controversy after the film’s release, with director James Cameron calling the film a “step backwards” for feminist cinema because it objectifies the body of Gal Gadot, who stars as the Amazon Princess Diana, “Wonder Woman”9. Patti Jenkins, the director of Wonder Woman, justified Gal Gadot’s costume, saying “That’s who she is; that’s Wonder Woman. I want her to look like my childhood fantasy”. Jenkins further responded that Cameron could not understand the film (which has been hailed by some as a “rare achievement for feminists in Hollywood”) “because he is not a woman”10. Indeed, Cameron seems to have missed the boat, focusing only on costumes but not on substance. By comparing the film to the ancient Greek legend of the Amazons as well as the Wonder Woman comics, I will demonstrate that the film, via the comic books, does bring a feminist portrayal of the Amazons, including the star Amazon, Wonder Woman, to the forefront. Like the original Wonder Woman story developed by William Moulton Marston, in conjunction with his wife Elizabeth Holloway Marston and his mistresses Olive Byrne Richard and Marjorie Wilkes Huntley, the film deploys the Amazon myth in a feminist manner, especially when contrasted with the ancient Greek legends of the Amazons. In some ways Marston stayed true to the myths of the Amazons, while in others he inverted the legends. In so doing, he argued for women’s rights, employment, and salvation from patriarchy. He used the Amazon myths as a background to bring a feminist message (and along with it, a positive portrayal of classical themes) to the masses, and this was no small achievement.

I will begin by examining the pertinent Amazon myths used by Marston and later Zack Snyder and Allan Heinberg, the author and screenwriter of the 2017 film script, noting their originary purpose in ancient Greek culture. Next, I will explore the reception of the Amazon myths in the original Wonder Woman comics, paying careful attention to the ways in which Marston adapted the legends to suit his feminist agenda, and, not without controversy, to incorporate his ideas regarding homoeroticism as well as bondage and domination into them. Finally, I will discuss the reception of the Amazons in the 2017 Wonder Woman film, underscoring the feminist achievement of the filmmaker and director in providing not just the first epic female superhero to hit the top of the box office, but also in incorporating a female gaze, and highlighting the physicality, autonomy, and social values of the Amazons in what may be dubbed the first world premier of Themiscyra, the legendary, utopian homeland of warrior women who freed themselves from the bonds of patriarchy.

The Amazons in Greek Lore and Iconography

The myth of the Amazons was used by the ancient Greeks for a variety of purposes, which changed over time. Like centaurs, giants, and other fantastic creatures, the Amazons functioned in myth as a means of marking cultural and sexual differences of imaginary beings from the Greeks themselves. Myth is “interpreted and reworked by every teller”, and is expressed through a communication process which, as Humphreys has noted, includes symbols “the relationship of which is not explicitly made in narrative but is supplied by the social experiences of the audience”11. The Greeks considered myth to be instructive, providing “examples with known outcomes for imitation or avoidance”12. While it is beyond the scope of this paper to give an exhaustive account of the Amazon myth and its uses within Greek culture, I shall here focus on those aspects of the legends that are incorporated, in one way or another, into the Wonder Woman comics and film.

The Amazons appeared in the earliest Greek literature, including the Iliad of Homer and the Aithiopis of Arctinus. In Homer (Iliad 3.189, 6.186), the Amazons are called antianeirai, or “the equals of men”. The noun Amazones is thought to be an ethnic designation, which, under other circumstances, would be masculine. It is unusual in that it is treated gramatically as a plural feminine noun, being modified by the compound adjective, antianeirai, which, due to its unusual feminine ending (-ai) is unambiguously feminine13. The Amazons of epic are a group of women only; the epithet antianeirai precludes any idea that this “ethnic group” included men. Whereas the gendered division of labor in epic is generally absolute (e.g. Hom. Il. 6.490-3), the Amazons are an exception to this rule; they fight and make war like men. As they are the equals of men, heroes “have to prove their privilege” with respect to these rivals14. In the Greek mindset, Amazons are women who perform the feats of men15. Arctinus’ Aithiopis is no longer extant, but a fifth-century summary of it by Proclus (Chrestomathia 2) gives us a hint of what it once said: “The Amazon Penthesilea, daughter of Ares, Thracian by race” came to the aid of the Trojans who were then besieged by the Greeks16. Penthesilea is called a daughter of Ares, thus suggesting that she is divine, or at least semi-divine, unless, of course, the phrase is metaphorical17. Apollonius of Rhodes explains that the Amazons were the offspring of Ares and the nymph Harmonia, and that they “were exceedingly savage and knew not that which is right” (Argonautica 2.991-2). In any event, although she acts heroically [aristeousan], Penthesilea is killed by Achilles. Hardwick asserts that “the Amazons had a stock role as an index of heroic achievement. Their figurative importance is the product of an aristocratic way of looking at the world”18.

Similarly, Heracles fought the Amazons as a mark of his aristeia, which translates to “excellence” or “prowess”19. The ninth of his twelve labors, which he performed to satisfy Eurystheus, was to retrieve the zōstēr of the Amazon queen Hippolyte. The term zōstēr is often translated as “girdle,” but appears to have referred more so to a warrior’s belt20. While Heracles (Hercules in Latin) forcibly takes Hippolytye’s zōstēr from her in many versions of the myth (e.g. Diod. Sic. 2.46.3-4; Pausanias 5.10.9; Quintus Smyrnaeus Posthomerica 6.240-45; Hyginus Fabulae 30), in other versions Hippolyte gives Heracles her belt willingly. (This she also does in the 1942 comic book Wonder Woman #1, as I will discuss below). In one instance, she does so to ransom another Amazon who has been captured by Heracles (Apollonius of Rhodes 2.966-69), but according to Pseudo-Apollodorus (Bibliotheke 2.5.9), she went to Heracles’ ship to greet him upon his arrival. Learning that he had come for her zōstēr, she offered to give it to him. But Hera, Heracles’ nemesis, sowed discord among the Amazons, who attacked the ship. Fearing that Hippolyte had betrayed him, Heracles slew her and took the zōstēr.

Whether Heracles’ intention was to seduce Hippolyte, force her to sexually submit to him, or simply to kill her and bring the belt back as proof, depends upon which version of the myth one subscribes to. Although the literary sources on Heracles’ Ninth Labor date from the Classical, Hellenistic, or later periods, the combat between Heracles and the Amazons is depicted on numerous archaic Greek vases21. Whereas a number of scholars assert that Heracles sought to take Hippolyte’s zōstēr, and her virginity along with it, Bremmer asserts that a translation of “girdle” for zōstēr is imprecise22. According to the LSJ, a zōstēr is both “a warrior’s belt, probably of leather covered with metal plates” and, later, the equivalent of a zōnē, a woman’s belt, which is defined as “the lower girdle worn by women just above the hips”23. The zōnē was “a much lighter and more decorative attribute” than the zōstēr24. At the temple of Athena Apatouria, young girls would offer their zōnai to the goddess before marriage (Paus. 2.33.1). When the young women became pregnant, they would in turn be offered zōstēres. Thus the zōnē would appear to have been the “chastity belt” of a virgin, but a zōstēr could be worn by a chaste wife, at least in certain contexts.

While the two terms may have been used interchangeably in other contexts, it would make more sense for Hippolyte, a warrior woman, to wear a zōstēr. Regardless, wearing such protective armor and fighting would protect her chastity from invaders. Bremmer notes, however, that Heracles never approaches, and hence never penetrates Hippolyte in extant vase paintings25. Dowden, more convincingly, suggests that rape could have been part of the conquest26. The loosening of the “girdle” or “belt” (however one chooses to translate zōstēr) is suggestive of a sexual act.

Heracles had been accompanied by Theseus in some versions of the myth, and Theseus was known for his capture of and marriage to the Amazon Antiope (though in some versions Hippolyte takes Antiope’s place). There are two versions of the tale of Antiope and Theseus of which I am aware. In one version of the myth, Antiope is abducted by the beguiling Greek Theseus, but in another she falls in love with him. (Wonder Woman’s departure to the “world of men” is a modern version of the tale of Antiope, the Amazon who leaves Themiscyra, albeit one which gives women more agency, a point to which I will return below). Pausanias (1.2.1) relates both traditions: “Pindar says that this Antiope was abducted by Peirithous and Theseus, but Hegias of Troezen writes an account of her as follows: Heracles was besieging Themiscyra on the Thermodon but he was not able to take it. Antiope, however, having fallen in love with Theseus – for Theseus was at that time campaigning with Heracles – surrendered the city”. In Pindar’s version, Antiope is a helpless captive (though the Amazons do attack Athens in retaliation), whereas in Hegias’ version, she is a traitor to her sister Amazons. Wonder Woman takes bits from Hegias of Troezen’s account, and that of Bion as preserved by Plutarch (Theseus 26.2): “And Bion says that even this [Amazon: Antiope] he [Theseus] took by deception: for the Amazons being by nature friendly to men did not flee from Theseus when he landed on their shores, but sent him gifts; he summoned the one who brought the gifts to board the boat; she embarked and he put out to sea”27.

As a result, the Amazons attacked Athens to recover Antiope. The Amazons were ultimately either defeated by the Athenians, as in Lysias (2.5), or unable to take the city, and signed a truce, as in Plutarch (Thes. 27). Whereas the purpose of the Amazons in heroic episodes was to “embellish the virtues and achievements of the heroes”, once they left their homelands and marched upon Greece, their purpose seemingly morphed into serving as an outside other against whom Greek superiority could be measured28. Yet, from the perspective of the Amazons, the account of the invasion depicts the importance of sisterhood among the Amazons, a theme that would be reiterated in the Wonder Woman comics and 2017 film, both literally and figuratively. According to Pausanias (1.16.7), Antiope’s sister, Hippolyte, led the Amazons to Athens to fight for the return of Antiope. Having been defeated by the Athenians, Hippolyte escaped with the few remaining Amazons to Megara and there died of a broken heart. Furthermore, according to Lysias (2.4-5), although the Amazons were successful in subduing barbarian men – largely because they had invented the use of iron weapons and were the first of their kind to ride horses – they were ultimately defeated by the Athenians. Lysias asserts that “when they encountered noble men, they acquired spirits like their nature; and... they appeared to be women”29. Whereas the Amazons prior to defeat “serve to expose tensions within the societal division between the sexes in terms of roles and attributes”, after defeat, “their weak, feminine nature is paramount”30.

The Amazonomachy, the battle between the Amazons and the Greeks, was an important decoration on both vases and public monuments, especially after the Persian invasion of Greece31. The details of the Amazon invasion are similar to those of the Persian invasion; hence the latter account may have inspired the former (Paus. 1.15.3; Hdt. 8.52)32. Amazons are sometimes depicted wearing Persian trousers in vase painting, though this may occur before the Persian invasion, ca. 500 BCE33, although perhaps not before the Ionian uprisings in 499/98 BCE, supported by the Athenians, that precipitated the Persian invasions of Greece.

Whether Amazons in Greek myth should be treated as an external threat, as analogous to barbarians (especially after the Persian invasions of 490 and 480/79 BCE), or as an internal threat, analogous to Greek or Athenian women, is a matter of much debate34. The frequency in which Amazons are “vanquished” on Attic vases may have some correlation with the declining status of women in Athens during the 6th century BCE, as Athens transitioned from being an oligarchy to a democracy35. In Greek art, the Amazonomachy reinforced patriarchy’s assessment of women as inferior to men. On an Attic red-figure volute krater, dated to ca. 470-460 BCE and attributed the Painter of the Woolly Satyrs, an Amazon who is about to be killed has an exposed breast (fig. 1). The revealed breast indicates her vulnerability36

.

Fig. 1

Amazonomachy on a red-figure volute krater attributed to the Painter of the Woolly Satyrs. The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Rogers Fund, 1907; 07.286.84.

Retrieved on August 1, 2019 from https://library.artstor.org/asset/SS7731421_7731421_11655928

Similarly, one breast is exposed on the Landsdowne Amazon, and her chiton is drawn up (fig. 2). Stewart asserts that her depressed demeanor indicates that “she has clearly been raped”37. Havelock argues that the message to women was “behave like an Amazon and you will be overcome”38. From a male perspective, such depictions probably had an erotic significance39, although the sensitivity of expression suggests that we look beyond the eroticism.

Fig. 2

The Landsdowne Amazon. Marble; 1st-2nd century A.D. The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1932; 32.11.4.

Retrieved on August 1, 2019 from https://library.artstor.org/asset/SS7731421_7731421_11780326

In Herodotus (4.114), whose interests were geographical and ethnographic in addition to historical, the Amazons are represented as the polar opposites of Scythian women, who, in turn, are seemingly projections of Greek women40. Herodotus (4.110-113) tells us that after capturing the Amazons at Themiscyra, in retaliation for their attack upon Athens, the Greeks set sail to take the captive Amazons back to Greece. The Amazons, however, mutinied and killed all of the Greek sailors. As they did not know how to sail, being equestrian, not maritime women, they drifted to Scythia. Not knowing how to return to Themiscyra, they set up camp on the shores of Scythia. The Amazons next encounter young Scythian men, and the two groups decide to partner with one another. As they discuss the terms of their unions, the Amazons assert that they cannot live with the Scythians, because Scythian women live in wagons and perform only “women’s work”, whereas the Amazons shoot the bow, throw javelin, and have never learned said “women’s work” (4.114)41. Thus, they convince the Scythian men to leave their families of origin, and to form a new tribe, the Sauromatians. The Amazons’ assertion places them in “direct opposition to the then developed conventions of the Greek oikos”42. They were thus an “other” through which the Greeks defined their own norms.

In Greek “literary discourse, the metaphor of marriage, as a founding and sustaining act of culture, was set against that of war, polemos. Equals were to exchange women; those outside the circle existed in an agonistic relationship to the body of citizens”43. Women were necessary to reproduce the polis but were not allowed to participate fully in the political process. Part of the project of the Greek polis was to control women’s reproduction. This was fully realized with the passage of Pericles’ citizenship law of 451/50, which allowed Athenian men to marry only Athenian women whose fathers were Athenian citizens and mothers daughters of Athenian citizens. Aeschylus calls the Amazons “parthenoi fearless in battle” [machas atrestoi], “man-hating” [stuganores] and “manless” [anandroi] (PB 416, 723-4; Suppliant Women 287)44. They reject marriage, the ultimate destiny for a Greek woman, thus defining her through opposition. In Greek patriarchy, marriage was used to control the sexuality of women and ensure the legitimacy of offspring45. Marriage was associated with civilization and hence culture by the Greeks; those who refused it were not civilized, not cultured, and, ultimately, not Greek46. The Amazons are vanquished in Greek literature and art because they refuse marriage47. They control their own bodies, and do not allow men to do so for them48.

In fact, the first-century BCE historian Diodorus presents the Amazons not as a single-sex, separatist society but rather as the dominators of men in a matriarchal setting49. Diodorus (2.45.1, 3.55.1-2) calls the Amazons an ethnos gynaikokratoumenon, or a “nation ruled by women”50. Diodorus elaborates upon this idea, asserting that the Amazons took the roles of men in their societies, and broke the legs of their male relatives, thus forcing them to be domestic laborers. Thus the roles of both women and men were reversed in this later version of the myth. It is not apparent why the Amazons morph from a single-sex society of women only into a matriarchy, although Ken Dowden suggests that “without men at all, they are an un-society, an impossible society, which it is the job of ethnographers to convert into viable (but unattested) matriarchies. From the perspective of actual societies, Amazons are only part of a society masquerading as a whole”51. That women might rule over men was appalling to Heracles, thus he attacked and defeated the Amazons according to Diodorus (3.55.3)52. Hence, the Greeks saw the Amazons as a threat to patriarchy.

Although the Amazons are dressed as men on many Greek vases, their Greek opponents are often nude, both on vases and in reliefs. Nudity expresses heroism and invulnerability, and is seemingly suggestive of Greek male superiority53. Whether the Amazons shunned men or dominated them, the Greek myths seemingly present them as a menace. The Greek male was centered in the Amazon myths and art; he was the subject whereas Amazons were objects, so to speak. Yet there is also potentially a message of female independence and empowerment that lurks under the surface of the Amazon legends, if only these women could resist defeat and survive54. William Moulton Marston, the creator of Wonder Woman, would tap into that potential in his later repurposing of the Amazon myths.

William Moulton Marston and the Women Who Influenced his Feminism

In the comic books that he wrote, Marston used both the Amazons, and, of course, his own creation, the Amazon Diana who becomes Wonder Woman, to illustrate his theories of female superiority. Marston was a first-wave feminist, at least in the sense that he ascribed to essentialist notions of gender55. He argued that peace would only be possible when men learned to submit to a loving authority: women56. He further suggested that the world would ultimately become a matriarchy, although he predicted this would only happen 1,000 years into the future57. Only women had the temperament to create peace; men were too prone to competition, anger, and ultimately war. Before detailing how Marston used the Amazons to illustrate his theories in the Wonder Woman comics58, I will briefly discuss Marston’s career prior to Wonder Woman, and his personal life. Both of these factors were important influences in his adaptation of the Amazon myths and his creation of the Wonder Woman character. Although Marston is given all the credit for creating Wonder Woman, the idea for her originated with his wife, Elizabeth Holloway Marston, according to their son59. Furthermore, Marston and Holloway lived in a polyamorous relationship with two other women: Olive Byrne Richards and Marjorie Wilkes Huntley. These women also seem to have contributed to the creative process of developing Wonder Woman, and also served as inspirations for Marston’s stories.

William Moulton Marston was born and raised in Massachusetts, as was his wife Elizabeth Holloway. The couple met at a grammar school in Cliftondale, and were married in 191560. Elizabeth earned a bachelor’s degree from Mount Holyoke College, a progressive women’s institution, where she studied Greek and was particularly fascinated by the poetry of Sappho. At Mount Holyoke, she was exposed to cutting-edge ideas and became both a suffragist and a feminist61. Suffragists sought the vote for women (a singular goal), whereas feminists sought broader rights for women, including full political rights but also the right to work62. Feminists rejected the idea that women had no sexual appetite and sought the right to use birth control, thus keeping sex separate from reproduction. The term feminist had come into wide circulation by 1913, and overlapped with the concept of a modern “Amazon”. The term “Amazon” was used to describe women who left home to seek higher education, thus positioning themselves to later become part of the work force63. In the nineteenth century, J. J. Bachofen had included the concept of the Amazons in his description of prehistorical matriarchy, a promiscuous phase that preceded the development of patriarchy. These theories appealed to suffragists and feminists, and were used as evidence that women were as capable as, or even more capable, than men64. First-wave feminists modified the myth of matriarchy, however, to remove the promiscuity from the matriarchal phase of civilization65.

Marston was also a suffragist; in fact, he was a member of the Harvard Suffragists’ club. He and Holloway went on to law school after completing their bachelors degrees, and he obtained a Ph. D. in Psychology from Harvard as well. He is credited by some as being the inventor of the lie detector test, which shows up in the Wonder Woman comics both as itself, and as Wonder Woman’s golden lasso, which is more than a lie detector test66. It compels the person it binds to do whatever the binder commands, including – but not limited to – telling the truth67. After his marriage to Sadie Elizabeth Holloway, who changed her name to Elizabeth Holloway Marston, William Moulton Marston met a young woman named Olive Byrne while teaching at Tufts University68. She was a student in his class. Byrne became Marston’s research assistant and lover. She was the niece of the renowned suffragist, birth-control activist, and author, Margaret Sanger, and daughter of the famous Ethel Byrne, who had almost died from engaging in a hunger protest while imprisoned in New York State for her role in opening a birth control clinic in Brooklyn. Marston introduced her to Elizabeth, and ultimately insisted to Elizabeth that he wanted Olive to move in with them. When Elizabeth said no, he threatened to leave and divorce her, so she finally gave in. In the 2014 biographical film, Professor Marston and the Wonder Women, the relationship between the two women is depicted as a lesbian love affair, or, perhaps better stated, as a menage-a-trois with William Marston. Elizabeth’s initial reluctance to have this polyamorous, live-in relationship is attributed to fear of gossip and societal, homophobic reprisal. The evidence does not necessarily support this “reading”, though it remains a possibility69. Elizabeth desired to continue working, but also wished to have children. By agreeing to bring Olive into the relationship, she was able to continue her career after giving birth, because Olive stayed at home to care for the children70.

Olive wore bracelets, which were surely the inspiration behind Wonder Woman’s bracelets that repelled bullets71. Her aunt and mother, both staunch feminists, surely were inspirations for Wonder Woman as well72. Although she falls in love with Steve Trevor, Wonder Woman resists his seductive efforts, and embodies economic self determination by working to support herself as Diana Prince (in addition to disguising herself).

Marston left Tufts at the end of the spring semester in 1926. It is not known whether he was fired, but this seems highly probable. He took a position as a lecturer at Columbia University, but learned in early 1928 that his position would not be renewed for the following academic year. He applied for a position at Harvard, but a damning letter of recommendation sealed his doom, preventing him from ever holding a regular academic appointment again73.

Either Marston’s investigations into bondage/domination practices at a sorority, or his polyamorous personal life (which involved students, such as Olive Byrne, clearly), or both resulted in his being blacklisted from future academic appointment(s)74. In the 1920s, Marston, his wife Elizabeth, their live-in partner Olive, and Marjorie Wilkes Huntley, a third woman who sometimes stayed with the Marstons and seems to have been involved with them, attended a sex cult in Boston. Specifically, it was a “cult of female sexual power” held at the apartment of William Marston’s aunt, Carolyn Marston Keatley75. A 95 page diary records the proceedings of what Jill Lepore suggests may have been a “sexual training camp”76. The women were divided into “Love Leaders”, “Mistresses”, “Mothers”, and “Love Girls”. A Love Leader, a Mistress, and a Love Girl together formed a constellation. The diary refers to Marston’s DISC theory (Dominance, Inducement, Submission, Compliance, which will be discussed below).

In his published psychological works, in particular The Emotions of Normal People, Marston asserted that emotions such as “fear, rage, pain, shock, desire to deceive, or any other emotional state whatsoever containing turmoil and conflict” were not normal77. In contrast, he considered emotional responses that “produce pleasantness and harmony”, to be normal. In his Try Living monograph, targeted towards a more popular audience than The Emotions of Normal People, Marston argued that “love emotions”, specifically captivation and passion, lead to happiness78. Captivation is domination, “the active, attracting aspect”, whereas passion comes from the desire to submit to domination. Marston argued that there were four primary emotions: Dominance, Inducement, Submission, and Compliance (Hence the acronym DISC was used to describe the theory). According to Marston, the optimal emotions were inducement and/or submission. Those who can truly induce another psychologically will feel more satisfied than if they merely dominate another person with force. On the other end, if a person can willingly submit to the desires of another, that person will feel more satisfaction than if they merely comply with that person’s request with an unwillingness to fully submit. Inducement and submission were the positive emotions, whereas dominance and compliance were negative feelings. Inducement consisted of persuading the other person to submit willingly; dominance meant forcing someone who was unwilling to do something against their will. Marston later deployed Wonder Woman and her Amazon mother Hippolyte to instill these ideas in the American public.

Marston’s scholarship was based, in part, upon experiments that he had conducted on young women students at Tufts, where the women engaged in bondage, domination, and submission with one another and reported their feelings to Marston and his assistant, who was also one of his mistresses, Olive Byrne. Marston’s The Emotions of Normal People did not make a big splash, but his Wonder Woman comics published more than a decade later, certainly did. Marston used Wonder Woman as a vehicle to communicate his theories to the masses, and in this he was ultimately quite successful.

One might question Marston’s feminism, inasmuch as he engaged in what were then deemed (and certainly would now be deemed, especially in feminist circles) unethical practices, including being sexually involved with a student. And yet the Wonder Woman comics are considered to have paved the way for the later 2nd-wave feminist movement of the 60s and 70s, whose leaders, such as Gloria Steinem, grew up with Wonder Woman79. In the formative years of the Golden Age of Comics from 1941 to 1947, when the Wonder Woman comics were written by Marston, there was a decidedly feminist message delivered to the public. The Wonder Woman comics were immensely popular and had a large readership. Admittedly, 90 % of the readers were male, and, although the original Wonder Woman artist, Harry G. Peter, did not portray a hypersexualized Wonder Woman, later artists certainly would. As DiPaolo notes, “artists and merchandisers have sold Wonder Woman posters, action figures, and comics that represent her as a wet dream in a star-spangled thong and not [as] a “real” woman with a life beyond the one conferred on her by a lecherous male gaze”80. This quote is particularly applicable to later renditions of Wonder Woman, most especially those drawn by Mike Deodato, Jr., where Wonder Woman is wearing a thong81.

The original Wonder Woman created by Marston and Peter is not wearing a thong, and Peter’s renditions of Wonder Woman are not hypersexualized like later versions of her. Her outfit, like those of her Amazon compatriots, was perhaps daring for the 1940s, when a woman was supposed to wear a skirt to her knees, although swimsuits and sportswear of that era were a bit more revealing. Wonder Woman’s outfit was designed to be patriotic, even if it did take the shape of a one-piece swimsuit for all intents and purposes. She was garbed in a red, white, and blue star-spangled outfit that announced her American patriotism loudly and clearly82. Marston surely understood that presenting a superhero who “was as beautiful as Aphrodite” would sell more comics83. The other 10 % of the original readers were girls, and those girls did benefit from the messages of empowerment contained in said comics, which I will discuss below. In an era when women wore skirts to their knees, Marston created a superhero who wore the equivalent of a bathing suit in public. Clothes can be confining, and part of second-wave feminism (women’s liberation) in the 1970s was about removing the confining layers of clothing and undergarments that hindered movement.

In a 1937 interview conducted at the Harvard Club in New York City, Marston predicted that “within 100 years the country” would see the beginnings of a trend toward “an Amazonian sort of matriarchy”. Within 500 years, he predicted a battle of the sexes for political control, and full-on matriarchy within 1,000 years84. In an interview conducted in 1942 by none other than Olive (Byrne) Richard and published in Family Circle magazine, Marston argued that women were “nature-endowed soldiers of Aphrodite, the goddess of love and beauty, and theirs is the only conquering army to which men will permanently submit – not only without resentment or resistance or secret desires for revenge, but also with positive willingness and joy!”85. When asked by Olive Richard (who interviewed “Bill” while pretending that she barely knew him) if men would ever stop fighting, Marston replied: “Oh, yes. But not until women control men”. Women had more love to offer than men, he asserted, whereas men had greater appetite. Appetite made men aggressive; submitting to women’s love would calm them. In any event, despite the rich panoply of both ancient and modern sources available to him, the core of Marston’s theory of matriarchy was developed from his own psychological theories.

Nevertheless, Marston used the Amazon myths to explain the origin of his superhero, Wonder Woman, and to reinforce his philosophy of matriarchy. It is clear that Marston knew of these myths. His version takes bits and pieces of the various myths, collects them together, and modifies them to suit a more feminist agenda than what we see in the Greek sources. As I will discuss below, Marston’s feminism was complicated by his own fetishism, but nevertheless delivers a message of female empowerment86. As to Marston’s knowledge of the Classics, several sources arise. First of all, long after Marston’s death, his wife, Elizabeth Holloway Marston said that her husband “studied Greek and Latin myths in high school. With that as a background, you can see that it was part of his background, so to speak”87. Of course, an education in the Classics was par for the course in the early 20th century. Sheldon Mayer, an associate editor at DC Comics who worked on the Marston/Peter Wonder Woman comics, asserted that Marston “used the mythological business of the Amazon”, although “he took some liberties with it”88. His wife, Elizabeth Holloway Marston, had been trained in ancient Greek as a student at Dorchester High School and later at Mount Holyoke College. Ancient Greek was her favorite subject, and Sappho was her favorite author. In fact, she died at the age of 100 with a copy of Sappho’s poems on her bed stand. Their son, Pete Marston, asserted that Wonder Woman was Elizabeth’s idea. “Come on, let’s have a Superwoman”, she said to her husband Bill. “Never mind the guys”89. Of course, Marston could have (and probably did) read the sources in translation, if not in the original. But, as mentioned above, it also seems clear that the women in his life played a role in the creation of Wonder Woman, even though the details of how this happened remain somewhat of a mystery.

Marston also seems to have been influenced by Charlotte Perkin Gilman’s 1915 Herland, a story of Amazonian women living in Africa90. The men in their society had been killed off long ago, and the women procreate by parthenogenesis (asexual reproduction)91. A group of explorers discovers this lost land of self-sufficient women concealed in the African hinterlands and eventually marry some of the women. The tale has many elements of the stories of Antiope and Theseus, as discussed above. The introductory story of Wonder Woman takes elements from both the ancient sources and Herland, and possibly from Inez Gillmore’s Angel Island, a story of an island of winged women. The winged women on Angel Island are ultimately discovered by men, who clip their wings. The women transform from angelic creatures into Amazons. In other words, men took their freedoms away and give them no choice but to fight back. All of these early 20th century stories, of course, were inspired by the Greek myth of the Amazons. Transmission of classical myths may not be straightforward. That said, much of Greek myth does appear in the Wonder Woman comics, although it is repurposed to suit the needs of a modern context92.

The Amazons in Wonder Woman

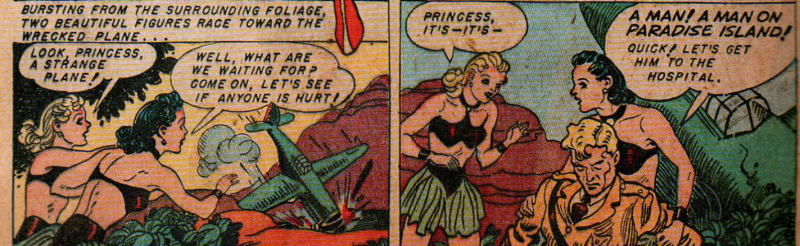

The Amazons of the comic series inhabit Paradise Island, where there are no men. That quickly changes when Steve Trevor crash lands and is badly injured (fig. 3). Emad notes that “When Capt. Steve Trevor’s plane mysteriously crashes on Paradise Island, this triggers the beginning of rendering the familiar strange and presenting utopian ideals for social reform, which Marston sets into motion with a gender-reversal image that becomes a continuous trope throughout the comic book’s history...”93. Diana saves Steve Trevor, falls in love with him, but takes the role of protector and guardian, instead of becoming hopelessly dependent upon him.

Fig. 3

“Introducing Wonder Woman”. All Star Comics #8 (Dec. 1941-Jan. 1942). Artist: H. G. Peter. DC Comics (Marston and Peter (2016a) 11)

At the command of Aphrodite, the Amazons decide to return Steve Trevor to the land of men. Princess Diana, the daughter of Hippolyte queen of the Amazons, insists upon taking him herself. But her mother Queen Hippolyte does not let her go easily; she is only permitted to do so after winning an athletic competition. This is also a gender role-reversal of sorts when compared to the story of the suitors vying for the hand of Helen through an athletic competition. As suggested above, Wonder Woman’s departure to the “world of men” is a modern version of the tale of Antiope, the Amazon who leaves Themiscyra, but with a difference in agency94.

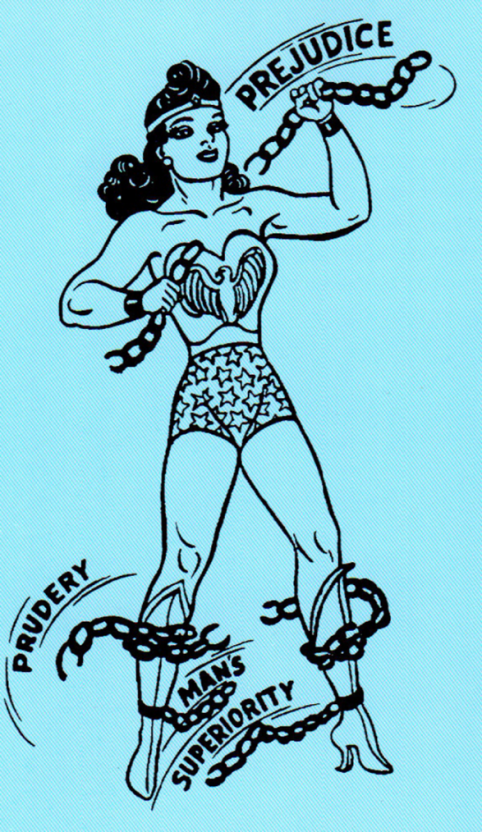

When Wonder Woman returns Steve to the army hospital, she accidentally drops a scroll that explains the origin of the Amazons95. The scroll, written in archaic Greek, is quickly deciphered by an archaeologist at the Smithsonian, one Dr. Hellas, who exclaims it to be the greatest find from antiquity yet. “The planet earth” begins the ancient script “is ruled by rival gods, Ares god of war, and Aphrodite, goddess of love and beauty”. “My men shall rule with the sword” exclaims Ares, whereas Aphrodite exclaims “My women shall conquer men with love” (fig. 4). Aphrodite’s prediction that her women will conquer men with love illustrates Marston’s theory of a future matriarchy, with men submitting to the loving authority of women96.

Fig. 4

“The Origin of Wonder Woman” Wonder Woman #1 (Summer 1942). Artist: H. G. Peter. DC Comics (Marston and Peter( 2016a) 149)

Ares is presented as “co-ruling” the earth with Aphrodite. Ares’ men then enslave the women. Marston narrates that, after the conquest of Ares, “Women were sold as slaves, they were cheaper than Cattle”. Thus Marston illustrates patriarchy’s exchange of women97. In response, Aphrodite created a “race of super women, who were stronger than men” whom she called Amazons. (This correlates, at least to some extent, to the early 20th century definition of “Amazons” as women who left the home, obtained an education, and worked, living independently. WAACS and WAVES (women in the armed forces) were called Amazons as well, perhaps unsurprisingly. Aphrodite then gave her own “magic girdle” to the Amazon queen, Hippolyte. Ares, who is now called Mars, is furious that Aphrodite had created new women stronger than men, and vows revenge against his sister. He thus inspires Hercules to make war on the Amazons98. Hercules, “the strongest man in the world”, challenges Hippolyte to a dual. Hippolyte’s magic girdle helps her to prevail over Hercules in battle, so he resorts to “treachery”99. At Hippolyte’s insistence, he swears not to attack the Amazons again, in exchange for being set free. He then invites the Amazons to a banquet in his men’s tents to seal their “pact of eternal friendship”. He then seduces Hippolyte and asks to hold her girdle, after she admits that “thou art strong as Ares – without this magic girdle I could never have conquered thee!”. After Hippolyte admits the source of her strength (the girdle) to Hercules, he makes his opportune move: “Let me hold thy girdle, O queen, just to touch it will send my spirits soaring since thou hast worn it”. “I ought not – but I cannot resist thee”, says Hippolyte, both wary of Hercules but yet love-stricken, as she hands the girdle over to Hercules. He then raises the battle cry, has his men seize and bind the Amazons, and Hercules commands the looting of their city, Amazonia. Hippolyte, helpless and in chains, next prays to Aphrodite, who takes pity on her, responding to say “You may break your chains, but you must wear these wrist bands always to teach you the folly of submitting to men’s domination”100. The Amazons now rise up against the Greeks, recover the magic girdle, board the Greek ships, defeat the Greeks guarding them, and sail away to Paradise Isle, where they build a “splendid city” (which, though not named in this origin story, would be labelled Themiscyra in later Wonder Woman comics and ultimately the 2017 movie).

The Amazons’ rebellion against their Greek captors in Wonder Woman #1 is reminiscent of the well-known story of the Amazons told by Herodotus (4.110-19), whereby the Amazons, taken captive by the Greeks on ships, mutiny against their captors. The Amazons do not know how to sail, and thus wind up in Scythia, where they marry Scythian men and form the new Sauromatian tribe. (This is the only ancient myth of the Amazons in which they defeat the Greeks of which I am aware). In Wonder Woman #1, the Amazons also rise up against their Greek captors, defeating them on land but also on their harbored ships. The Amazons then take the ships and sail to Paradise Island, led by Aphrodite. Aphrodite provides them a safe harbor, safe from men, that is. In a sense, Marston reverses the myth provided by Herodotus, as the Amazons begin by living among men, but wind up living alone.

Although much of the story of Hippolyte’s “girdle” is derived from Greek myth, the Marston version has a decidedly more feminist ending, with the Amazons prevailing and ultimately escaping from men rather than being defeated. Furthermore, the story serves as a warning for young girls and even older women readers not to trust men while simultaneously reinforcing feminist ideals of self-determination, bodily autonomy, and reproductive choice. Like Charlotte Perkin Gilman’s Herland, Paradise Island is a feminist utopia, where women are free from the chains of patriarchy, and war, caused by men, is not present.

Marston’s comics portrayed his philosophy and predictions. In Wonder Woman #7, Wonder Woman is allowed to see into the future on the Amazon “Magic Sphere”101. What she sees is herself being elected president102. This, of course, is what Marston had predicted, as the “Women’s Party” first defeats the “Men’s Party” in the year 3,000 A.D.

Wonder Woman fights misogyny. The dichotomy between good and evil, America and Nazi Germany, etc. is often boiled down to a battle of the sexes, such as Wonder Woman, representing America and its promotion of women’s rights, versus Ares, representing the war, the oppression of women, and, of course, the Nazis. Mars is more than just a god of war in the comic series, he is a representative of patronizing misogyny at its worst. In Wonder Woman #5, June/July 1943, we read that “Mars, the War God, present ruler of this World, receives unpleasant information from his slave secretary. “Here is the report you asked for – there are eight million American women in war activity. By 1944 there will be eighteen million!” “Hounds of Hades!” the sexist Mars retorts: “Women! This smells like more of Aphrodite’s work!”103. Mars is vehemently opposed to women working outside the home; he ultimately represents, in one sense, the oppression of women. In contrast, Wonder Woman urges women to “Get Strong” by joining the WAACs or WAVEs to “earn your own living”, thus reaffirming the feminist goal of economic self-determination for women.

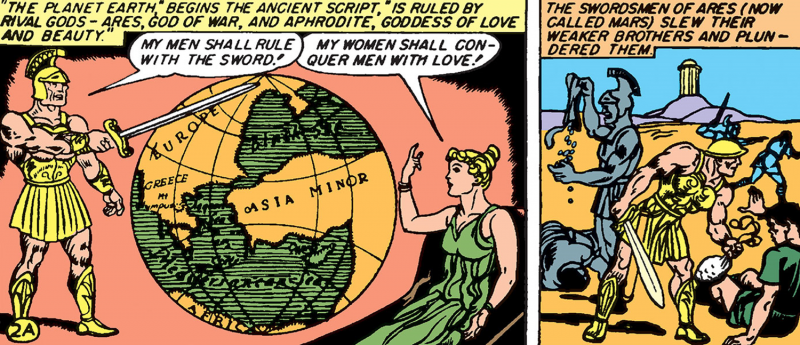

Wonder Woman strives to empower women on other levels as well, both physical and mental. In Wonder Woman #13, Diana returns to Paradise Island, where young Amazons have begun to doubt their own abilities “to perform superfeats”104. Wonder Woman encourages the girls, jumping 150 feet into the air and snapping chains. “You see girls”, she says, “there’s nothing to it!”. She is shown (fig. 5) in a 1943 illustration drawn by Harry G. Peter (the original artist of Wonder Woman) breaking off the chains of “Prejudice, Prudery, and Man’s Superiority”.

Fig. 5

Reprinted from The American Scholar, Volume 13, No. 1, Winter 1943/44. Copyright © 1943 by The Phi Beta Kappa Society

The drawing accompanied an article published by Marston in American Scholar, the journal of Phi Beta Kappa, which was entitled “Why 100,000,000 Americans Read Comics”105. Wonder Woman’s breaking free from such bonds harkens back to suffragists who wore chains during protests106. Lucy Burns, one of the leaders of the National Women’s Party who had been arrested multiple times in 1917, was beaten and chained to her jail-cell door107. She and her co-founder, Alice Paul, and others had gone on hunger strikes while imprisoned. Shortly thereafter, in January 1918, Woodrow Wilson finally announced his support for Women’s Suffrage. The suffering of these suffragists had not been in vain, even if it had been insufferable.

Amazons, Holliday Girls, and Sisterhood in Wonder Woman

Perhaps one of the most feminist aspects of Wonder Woman is her association with other women, both the Amazons and the sorority sisters of Beeta Lambda, the “Holliday girls”, who, for all intents and purposes, take the place of Diana’s sidekick Amazons in “the world of men”108. The sisters of Beeta Lambda assist Wonder Woman in apprehending various criminals. Like Amazons, they are tough and fearless; and none is tougher or more fearless than Etta Candy, Wonder Woman’s main sidekick and president of the Beeta Lambda sorority. The idea of women working together to further their own betterment is one of the underlying precepts of feminism. In fact, the most vocal of Wonder Woman’s critics, Fredric Wertham, who was certainly no fan of feminism, pointed this out in his invective. He reveals the anxiety that such sisterhood could invoke in men:

The homosexual connotation of the Wonder Woman type of story is psychologically unmistakable. The Psychiatric Quarterly deplored in an editorial the “appearance of an eminent child therapist... which portrays extremely sadistic hatred of all males in a framework which is plainly Lesbian”.

For boys, Wonder Woman is a frightening image. For girls she is a morbid ideal. Where Batman is anti-feminine, the attractive Wonder Woman and her counterparts are definitely anti-masculine. Wonder Woman has her own female following. They are all continuously being threatened, captured, and put to death. There is a great deal of mutual rescuing... Her followers are the “Holliday girls”, i.e. the holiday girls, the gay party girls, the gay girls. Wonder Woman refers to them as “my girls”109.

For Wertham, the homosocial environment of Holliday College, the cooperation among the young women, and, one might suggest, some of their kinky bondage and domination schemes, making pledges submit to them, as well as the “masculine” activities of apprehending criminals, all seemed to lead to lesbianism, a point to which I shall return shortly. While Wertham saw the camaraderie of young women as a threat, Gloria Steinem later saw it as novel and welcome:

Wonder Woman’s family of Amazons on Paradise Island, her band of college girls in America, and her efforts to save individual women are all welcome examples women working together and caring about each other’s welfare. The idea of such cooperation may not seem particularly revolutionary to the male reader. Men are routinely depicted as working well together. But women know how rare and therefore exhilarating the idea of sisterhood really is110.

Yet Steinem also noted that what Marston was arguing for was not really feminism, but rather “female superiority”. She writes:

Marston’s message wasn’t as feminist as it might have been. Instead of portraying the goal of full humanity for women and men, which is what feminism has in mind, he often got stuck in the subject/object, winner/loser paradigm of the “masculine” versus “feminine” and came up with female superiority instead... No wonder I was inspired but confused by the isolationism of Paradise Island: Did women have to live their lives separately in order to be happy and courageous? No wonder even boys who could accept equality might have felt less than good about themselves in some of these stories: were there any men who could escape the cultural instruction to be violent111?

Of course, the feminist separatism of the Amazons is derived directly from the Greek myths. In the stories of the Amazons told by Strabo (11.5.1), the women of the Amazons met with the neighboring tribe of the Gargarians only once a year to copulate. They raised the daughters, and gave the boys back to the Gargarians. Hellanicus (FGrH 4 F 167), calls the Amazons arsenobrephokontoi, or, “male infant-killing”, suggesting that they didn’t even give the boys away, but rather committed infanticide with them. The idea of “female superiority” can also be attributed to the myths as well. As noted above, Diodorus Siculus (2.45), relates that the Amazons lived in a matriarchal fashion, breaking the legs of their menfolk and making them perform domestic labor while the women fought and hunted. In other words, the world of Diodorus’ Amazons was an inversion of patriarchy, a matriarchy, and hence “inimical to civilization”112.

And whatever Steinem’s thoughts were on Paradise Island, the concepts of matriarchy and Amazons had broad appeal to feminists of the 1970s. In fact, the one thing that all feminists of the 1970s agreed upon, at least according to Hanley, was that they loved the Amazons113. That’s where the agreement ended; “the rise of lesbian feminism in the 1970s, for example, presented women with some very thorny questions about the noncontinuities between sex and politics and resulted ultimately in internal sex wars within feminist and lesbian and lesbian feminist communities”114.

Some lesbian feminists wished to live completely apart from men, just like the Amazons, and the comics of Wonder Woman may well have constituted their first exposure to the ideology of feminist separatism as young girls. These women joined with other “radical feminists”, establishing a platform that went beyond what the “liberal feminists” sought. Whereas the liberal feminist, like others, sought equal social and political rights as men, radical feminists argued that the only way to fight patriarchy would be to tear it down altogether115. Radical feminists argued that working with the government or participating in marriage and traditional child care could only keep women down. Some felt that pornography was demeaning to women, and sought to rid society of its influence. By avoiding marriage and having no interaction with men, women could be free of patriarchy. Of course, this worked better for lesbians than for others. By seeking to have an existence completely separate from men, these “radical feminists” were modern-day “Amazons” in the truest sense of the word. The Wonder Woman comics provided an example with visions of the utopian, manless Paradise Island.

Amazons and Love Binding

The Amazon society of Paradise Island was based upon “love-binding” among women, and between the goddess Aphrodite and the Amazons. The Amazon practice of bondage, domination and submission, of course, echoed Marston’s theory of emotions, as did those of the similarly homosocial Holliday girls. The homoeroticism in both groups is a subtext which can be read in, if the reader so chooses. In that sense, Wonder Woman is like films of its time; codes of conduct prohibited explicit mention of lesbian relations, but that did not stop authors, artists, and filmmakers from hinting at lesbian and gay themes which the reader or viewer could infer116. While there is no explicitly lesbian content in Wonder Woman, the implications are everywhere. Bondage and domination are recurring themes among both the Amazons and the Holliday Girls, with strong homosocial and homoerotic overtones.

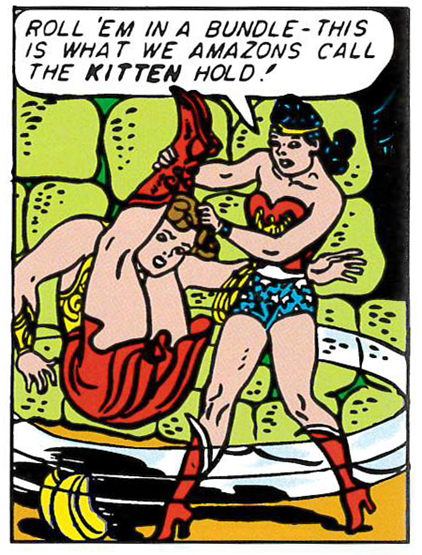

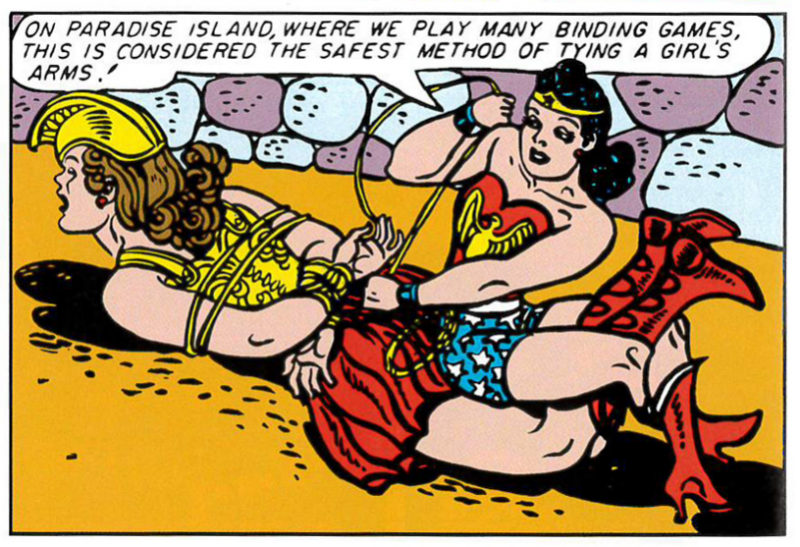

When visiting Atlantis in Sensation Comics #35, Wonder Woman subdues female guards. As she tackles and binds one of the guards, she exhorts: “This is what we Amazons call the kitten hold! On Paradise Island where we play many binding games, this is considered the safest method of tying a girl’s arms!”117 (figs. 6 and 7).

In figure 6, Wonder Woman, wearing high-heeled boots with her lasso tied to her belt, looks like a fashionable dominatrix. And while she handles the Atlantean guard somewhat roughly, pulling her head through her legs by the hair, her naming of the position as “the kitten hold” suggests erotic play, as well as Marston’s idea of submission to a loving authority. In figure 7, as she binds the other woman’s hands while sitting on top of her, Wonder Woman invokes the need for safety as part of an Amazon ethics of seemingly eroticized bondage play.

Fig. 6

“Girls Under the Sea” Sensation Comics #35. (November 1944) Artist: H. G. Peter. DC Comics (Marston and Peter (2017) 333)

Fig. 7

“Girls Under the Sea” Sensation Comics #35. (November 1944) Artist: H. G. Peter. DC Comics (Marston and Peter (2017) 333)

On Paradise Island the Amazons incorporate bondage into their worship of Aphrodite. They are willingly bound by Hippolyte to show their submission to her authority, and by Princess Diana as well. According to Hanley “The Amazons incorporated bondage into their society as an expression of trust to emphasize that their utopia was based on kinship with a hierarchy of submission. All of the Amazons were committed to their patron goddess Aphrodite; love was their very foundation”118. Since there are no men on Paradise Island, there is an homoeroticism suggested by all of this.

Bondage in the Wonder Woman comics, however, serves multiple functions. As noted above, it can be representative of patriarchy. The Baronness Paula von Gunther is enslaved to the Gestapo as an agent because they hold her daughter as a captive119. Similarly, her slaves are bound by “fascism” to her. They are forced into overcompliance, resulting in negative emotions per Marston’s theory of emotions, rather than being induced into willing submission, a far more pleasant experience per Marston. Wonder Woman theorizes that, “if girls want to be slaves, there’s no harm in that”, but explains that “the bad thing for them is submitting to a master or to an evil mistress like Paula! A good mistress could do wonders with them!”120. The kind of domination enacted by male masters is categorically rejected, and only one kind of dominator is considered fit for the task: a dominatrix. The slavegirls of Mars, a typical “sexist tyrant”, in the stories, eat on the floor and wear leashes like dogs121. “Theirs is a humiliating, dehumanizing bondage, quite distinct from the empowering Amazon kind”. Bondage is used among Amazons to express love and submission, although it is also used to detain villains, criminals, and other adversaries. Even then Wonder Woman is reticent to hurt others, however; she tends to bind her captives and then send them to Reform Island, where they are rehabilitated from their erring ways. This contributes to yet another feminist goal, the attainment of peace. In both cases, the use of bondage seems more in line with BDSM practices than it does with law enforcement, as in the latter case one might not have time to be “gentle” while apprehending dangerous criminals. BDSM is a “compact acronym which points to three intimately related, yet quite distinct practices. Each of these practices is designated by a pair of linked terms, and each pair of terms appears in the larger acronym: bondage and discipline (BD), dominance and submission (DS), sadism and masochism (SM)”122. Each of these three practices is unique, although there are clear overlaps from one to the next. Furthermore, the practice of BDSM, at least when following a scenario of “best practices” involves an ethical code of conduct. Similarly, when we see Wonder Woman tying up Atlantean guards, she follows an Amazonian code of conduct. This is not derived from any Greek source of which I am aware, but rather seemingly stems from William Moulton Marston’s own psychology and practice, a practice to which he was perhaps exposed by Marjorie Wilkes Huntley123. “For Marston, bondage was about submission, not just sexually but in every aspect of life. It was a lifestyle, not [just] an activity, and he used bondage imagery as a metaphor for this style of submission”124. Marston did not necessarily approve of sadism, the enjoyment of inflicting pain125. “The only hope for peace is to teach people who are full of pep and unbound force to enjoy being bound”, Marston wrote. Men desire to submit to women, because women are “nature-endowed soldiers of Aphrodite, goddess of love and beauty, and theirs is the only conquering army to which men will permanently submit”126.

Amazons on Paradise Island enjoy being bound; they often walk around with their hands tied. “Female dominance offered the key to a sustainable, loving, happy relationship. Male dominance, on the other hand, slid too easily into an oppressive, patriarchal configuration”127. Marston argued against Freudian assessments of female dominance and male submissiveness as unnatural and pathological128. In fact, he argued for the opposite, asserting that female dominance was the ultimate good.

Amazons, Holliday Girls, and Lesbianism in Wonder Woman

The homoeroticism in Wonder Woman is subtle, but can be inferred129. Etta Candy is Wonder Woman’s sidekick and head of the Beeta Lambda sorority, also called the Holliday girls. The Holliday girls serve as a “stateside substitute for the Amazons”130. In ancient Greek tragedy, the Amazons are described as anandroi “man-less” and stuganores “man-hating” by Aeschylus (Suppliant Women 287; Prometheus Bound 723-4). Like an Amazon, Etta expresses her lack of use for men in Wonder Woman #1. Etta Candy lives up to her name; she likes eating candy and is not concerned that it makes her plump. Diana chides her for her indulgence, saying “But Etta, if you get too fat you can’t catch a man –”, to which Etta replies “Who wants to? When you’ve got a man, there’s nothing you can do with him – but candy you can eat!” (fig. 8).

Fig. 8

“Wonder Woman Versus the Prison Spy Ring” Wonder Woman #1 (Summer 1942) Artist: H. G. Peter. DC Comics (Marston and Peter (2016a) 189)

Noah Berlatsky astutely notes that Etta is wearing a rather “butch” cowboy outfit (as is Diana, in her military hat, shirt, and tie, despite the skirt (the only military woman’s option at the time) and that Etta’s mouth is aligned with Diana’s crotch as she discusses eating “candy”. Lillian Robinson argues, seemingly sarcastically, that “Etta’s reply is categorical and seemingly free of double entendre”131. Berlatsky takes this to mean that rather than saying that “there is no sexy lesbian content” present in the panel, Robinson is actually arguing that there is such content visible to the reader if not to Etta herself. Berlatsky suggests that the eating of candy can be understood as a “direct and deliberate allusion to lesbian oral sex”, and further argues that any reading of this panel (and he offers three possibities) must be understood as powered by its “relationship to the closet”132. Even if Marston had intended for the scene to have lesbian overtones, they had to remain implicit rather than explicit. This was, after all, the 1940s and Marston was writing, ostensibly, for children. Nevertheless, “Etta’s disavowal of romantic interest in males is important”, as it points to a crack in the closet, so to speak133.

Yet there is one final point that must be noted about this panel. On the opposite side of the railroad car sits a man. While Diana Prince and Etta Candy pay him no mind (an interesting reflection given their respective statements), he stares over at the two young women, particularly at Etta. He is a voyeur who seems to be rather interested in the two women flirting, or, perhaps better stated, in Etta’s flirting with Diana134. Berlatsky suggests that the man could possibly represent Marston himself135. While Marston approved of female homoeroticism, he also saw it as part of a broader polyamory136. His approval of female homoeroticism may have stemmed, at least in part, from his own polyamorous relationship(s), though the evidence is not entirely conclusive137.

Yet another lesbian implication in Wonder Woman is the frequent invocation of the name of Sappho, although much of this, interestingly, occurred under later authors after Marston’s death in 1947. One of Wonder Woman’s stock phrases was “Suffering Sappho” (fig. 9).

Fig. 9

“Villainy Incorporated” Wonder Woman #28 (March 1948). Artist: H. G. Peter. DC Comics (Marston and Peter (2016b) 67)

Given Elizabeth Marston’s penchant for reading Sappho, the source of this phrase, like the idea of Wonder Woman herself, can probably be attributed to Elizabeth138. Sappho does directly mention the suffering of young women, who were presumably sent away from Lesbos upon their marriages. The most explicit of Sappho’s fragments suggests the loss that one of Sappho’s beloved is feeling upon her marriage, and hence impending departure from Sappho’s presence:

“I simply wish to die”.

Weeping she left me

and said this too:

“We’ve suffered terribly

Sappho I leave you against my will.”.

I answered, go happily

and remember me,

you know how we cared for you,

if not let me remind you

...the lovely times we shared.

Many crowns of violets,

roses and crocuses

...together you set before me

and many scented wreaths

made from blossoms

around your soft throat

...with pure, sweet oil

...you anointed me,

and on a soft, gentle bed...

you quenched your desire...

...no holy site...

we left uncovered,

no grove... dance

...sound139.

Sappho’s erotic and emotional involvement with other women is suggested by the remnants of her own work140. While there is some controversy over whether Sappho’s poems are autobiographical, in the early 20th century Sappho was extremely popular at women’s colleges, and the term lesbian, derived from Sappho’s place of origin, Lesbos, was increasingly used to describe women who were romantically and/or erotically involved with other women141.

To a classicist specializing in gender studies, the phrase “Suffering Sappho” makes a world of sense. But in the 1940s and 1950s, it was enough to cause an uproar. Indeed, after Marston’s death, Dr. Frederic Wertham published a book entitled Seduction of the Innocent, in which he purported that the Wonder Woman comics promoted lesbianism142. Marston had endorsed female homoeroticism in his published psychological work, The Emotions of Normal People, and the characters in Wonder Woman, especially Wonder Woman herself, tended to espouse his ideas, as I have discussed above.

In The Emotions of Normal People, Marston asserted that it was normal for young girls of the ages of “five or six years, or older” to experience passive love for other girls, “with or without mutual stimulation of the genital organs”143. Furthermore, he explicitly explained how two women could have clitoris-to-clitoris sex, otherwise known as tribadism144. Not even Freud had explained how such stimulation occurred; Marston describes the possibility of mutual genital stimulation between women as a “little known” fact145. He also asserts that “women’s expression of passion emotion in relationship with other women” is important in the emotional life of women146. “I was aware from personal observation that young women living together in a home might evoke from one another extremely pleasant and pervasive love responses, without bodily contact or genital excitement. Upon investigating, with the invaluable aid of my collaborators, the love relationships between girls and women outside the influence of college authorities and home life, however, I found that nearly half of the female love relationships concerning which significant data could be obtained, were accompanied by love stimulation”147.

The Reception of Amazons in the 2017 Wonder Woman Film

Patti Jenkin’s 2017 film presents the Amazons in an archaizing fashion. They wear leather armor and use swords and bows and arrows instead of guns (as compared to the Amazons of the 1940s Wonder Woman comics, who do have guns, airplanes, and other current and even fantastic technology, such as a “magic sphere” which can even see into the future). The most impressive of Wonder Woman’s attributes, the golden lasso of truth, is seemingly more magical than technological. It is also not an aspect of Greek myth but rather stems from Marston’s life: he invented, or was at least one of the inventors, of the lie detector test148. In the movie, the Amazons use their golden lasso to extract the truth from Steve Trevor as to his identity.

Steve is an interloper in what certainly counts as a “queer” world – that of women who shun men, the Themiscyra of ancient Greek lore. The film nonetheless quickly dovetails into heteronormativity as Diana falls in love with Steve Trevor. Yet it at least seems to be a feminist version of heteronormativity. Diana is ultimately the protagonist, though Steve Trevor is more of an equal to her (minus her superpowers) than the Steve Trevor of Marston’s comics, who plays more of a “damsel in distress” role than that of a co-eval. Diana’s evolution from a young child to a grown, wise woman fits fairly neatly into a narrative pattern of the hero’s journey, or, perhaps better stated, the superhero’s journey149.

In this, the casting of a woman in a role usually reserved for a man, and also in its cinematography, the film is decidedly feminist. Patti Jenkins uses what has been termed in Hollywood as the “female gaze”, as opposed to the “male gaze” as theorized by Laura Mulvey in her canonical 1975 essay150. Mulvey argued that the typical film had used a male perspective in filming, with women typically being objectified and eroticized as passive characters in contrast to dominant male figures. The “male gaze”, Mulvey argues, is not limited to the viewer but exists within the film itself, with male actors doing the looking and women being looked at. Wonder Woman, in contrast, employs the “female (Amazon) gaze” most notoriously in one scene, where Diana does the looking151. She gazes at an athletic, handsome, and naked Steve Trevor, played by Chris Pine. Steve Trevor is also the object of the viewer’s gaze (minus his genitals, which only Diana has the pleasure of viewing)152. (Diana, despite Cameron’s criticisms mentioned in the introduction of this paper, is not shown naked). When Diana walks in on Steve Trevor naked as he has just finished bathing in one of Themiscyra’s luminescent pools, she asks him “What is that”? When Steve demurs from commenting on his private parts and points to his watch, noting how it tells a man when to sleep, eat, and do everything else on a schedule, Diana wittily replies how amazed she is that men allow such a “little thing” to control their lives. The sexual innuendo of her comment is not lost upon the audience.

The film is shot from the viewpoint of Diana; Steve is a sidekick if also a co-eval. As the film begins, Diana views an old photograph of herself, Steve, and their compatriots from World War I. Diana is centered in our viewing of the picture, and the viewer is pulled into her centrality as the camera fades into her childhood at Themiscyra. Themiscyra is an Amazon paradise, where women train for warfare daily. It is like a female-only vision of Sparta.

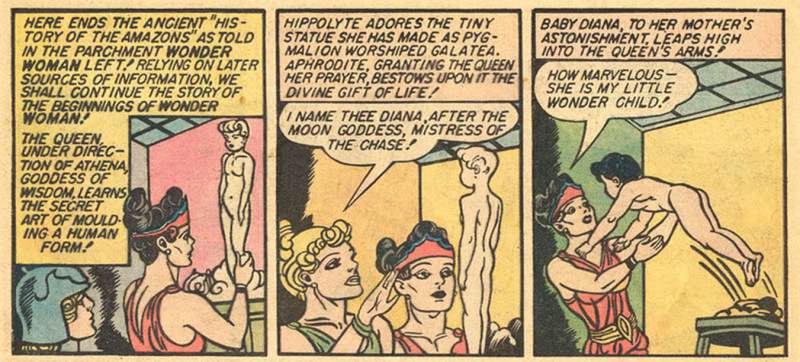

As she falls in love with Steve and yearns to leave Themiscyra to find and fight Ares, we quickly learn that Diana is no ordinary Amazon. In fact, though she is raised by the Amazon queen Hippolyte and trained to be a formidable warrior by her aunt Antiope, Diana turns out to be more than an Amazon. Diana, we learn, lives up to her Roman name: she is a god. (In true 21st century feminist fashion, she is called a god instead of a goddess). While she is told by Hippolyte that she was molded from clay, she later learns from Ares that she is the daughter of Zeus. Both of these ancestries come from the comic series. In the initial Wonder Woman, written by William Moulton Marston, Diana was made from clay like Enkidu or Adam, yet it was Aphrodite (not Zeus, as in the film) who breathed life into her as this comic strip (fig.10) portrays153.

Fig. 10

“The Origin of Wonder Woman” Wonder Woman #1 (Summer 1942) Artist: H. G. Peter. DC Comics (Marston and Peter (2016a) 153)

In a much later (2011) version of the New 52 Wonder Woman series, however, Diana is heralded as the daughter of Zeus and Hippolyta154 (fig. 11).

Fig. 11

DC Universe Rebirth: Wonder Woman Vol. 1 The Lies Artist: Liam Sharp. DC Comics (Rucka, Sharp, and Martin (2017))

This would normally have made her a demi-god in Greek myth, but in the 2017 film we are told only that she is the daughter of Zeus who was raised by Hippolyte. Her birth mother remains unknown. In any event, Diana defeats Ares and stands as the last of the Olympians155. This is yet another feminist feature of the story. Whereas Xena killed off a number of the Olympian gods, usually such a job is done by a male protagonist on the silver screen156. The death of the gods is a motif used by filmmakers to better relate to modern audiences, who are more used to monotheism. The idea that a woman, Diana, is the only god in the universe is striking. Thus, Diana, as the last of the Olympians, is certainly no ordinary Amazon.

And if we wish to call Diana an Amazon at all, then she is a “modern” Amazon. Between the comics and a pacifist Hollywood vision, the altruistic mission of the Amazons is to defeat war, or perhaps better stated in mythological terms, Ares. This flies in the face of Apollonius of Rhodes’ description of the ancient Amazons’ bellicose nature:

For the Amazons, those who dwell on the Doiontian plain, were exceedingly savage and knew not that which is right; rather grievous hubris and the deeds of Ares are their concerns: for they are the offspring of Ares and the nymph Harmonia, who to Ares bore war-loving girls (Argonautica 2.987-992).

Despite a change in mission and geneology, the Amazons of Wonder Woman do remain fierce. In perhaps the scene most reminiscent of Greek legend, an Amazonomachy, or battle between Amazons and men, Diana and her aunt Antiope lead the Amazons to victory over Germans, instead of the Greeks. Refreshingly, the Amazons defeat the Germans, whereas in Greek sources they are often, though not always, defeated by men157. This is certainly a feminist turn.

The choreography of the Amazonomachy, fought on the beach of Paradise Island, displays the incredible agility and ability of the Amazons as warrior women. Amazons seemingly fly off of the cliffs (using ropes), aim their arrows with deadly precision, and kick butt. Like Xena, the Warrior Princess (an interesting television precursor to Wonder Woman), the Amazons give deadly high-flying kicks158. Their athletic feats are particularly impressive, jumping, spinning in the air, and shooting with precisce, deadly aim. The Amazons are depicted here as truly powerful, and exceptionally skilled. Their practice with arms pays off; they defeat a mechanized German army with archaic weapons and incredible athletic ability.

DC Comics drew heavily on later versions of the comics when dressing Wonder Woman, as the comparison here shows (figs. 12 and 13).

Fig. 12

From: DC Universe Rebirth: Wonder Woman Vol. 1 The Lies Artist: Liam Sharp. DC Comics (Rucka, Sharp, and Martin (2017))

Fig. 13

Gal Gadot as Wonder Woman in Wonder Woman (2017) DC Films/Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc

Some comments on their inspirations for the costumes of the other Amazons were published in a Dec. 28, 2017 Vanity Fair newsletter:

Batman v Superman costume designer Michael Wilkinson wanted Wonder Woman to wear something specifically made for battle in the film that introduced the character to the D.C. cinematic universe. Patty Jenkins and Lindy Hemming then upped the ante on his original work in Wonder Woman, drawing inspiration from training armor, ancient cultures, societies run by queens and female warriors, and athletic trends. Hemming wanted her Amazons to be striking and strong, above all else – and she made sure to give them metal breastplates, a nod to mythology, in which Amazons cut off their left breasts to better wield their bow and arrows. Some of the Amazon warriors can be seen with a special breastplate on their left side, and many also protect themselves with armor on their knees and forearms, as well as metal headdresses. Their skirts are short for the sake of movement, resembling the design of Hoplite soldier wear, or pteruges, leather skirts worn by ancient Greek and Roman soldiers159.

A pterux is defined in the standard Ancient Greek-English lexicon as “the flap of a cuirass”160. The cuirass is typically the armor that protects the chest. The flaps would hang down from it covering the groin and buttocks. These types of flapped, skirt-like garments were, indeed, worn by Greek and Roman warriors – in fact, Alexander the Great is depicted wearing one in the famous mosaic of the Battle of Issus now stored in the Museo Nazionale Archaeologico in Naples161. Wonder Woman’s outfit is also equipped with pteruges, and the outfits of all the Amazons are reminiscent of the short chitons worn by Amazons on Greek vases (see fig. 1 above). Thus the costumes do have an authenticity to them, although one inspired from Amazons wearing Greek outfits, rather than Thracian, Scythian, or Persian outfits with trousers. In Justice League, the Amazons do wear somewhat more revealing outfits, showing off their abs, but considering how ripped some of these women are, the effect works. One expects an Amazon to be strong. The fishtail braids worn by the Amazons also find a counterpart on ancient Greek statuary, if not in representations of Amazons themselves162.

The multiracial Amazons of Wonder Woman (2017) also fit into a third-wave feminist aesthetic. Whereas liberation and equality were the central tenets of Second Wave feminism (or the Women’s Liberation Movement, starting in the 1960s), Third Wave feminism can be defined as incorporating diversity and individuality163. Whereas Second Wave feminism was critiqued for centering the white, middle class, heterosexual woman, Third Wave Feminism strove to embrace inclusion and understanding of difference among women of various ethnicities, races, and sexual orientations. Wonder Woman’s feminist leanings waxed and waned over the years after William Moulton Marston’s death in 1947 (mostly for the worst). Although her transformations have often, if not always, “mirrored those of her flesh-and-blood ‘sisters’: her metamorphoses reflect nothing less than the confusion, fear, and constant reformation of American ideals about American women”164. When George Perez drew Wonder Woman, from 1987 to 1992, he made her look more “ethnic” as after all, she was not an American woman but rather an Amazon. Perez also drew the Amazons as more racially diverse, a welcome upgrade that the film would later replicate.