Freed slaves formed a conspicuous group in Roman Italy. Though looked down upon because of their servile past, many of them were highly successful in craft and commerce amassing great wealth and leaving a lasting mark on Roman society. Their ambiguous social position is reflected by the stereotype of the wealthy parvenu as personified by Trimalchio in Petronius’ Satyricon.1 Yet, their ubiquitous funerary monuments and inscriptions tell a very different story. Freed families could not boast ancestor galleries or a dignified past. For recognition of their achievements they looked at the present and the future. Their funerary monuments show pride in their hard-won freedom, their newly acquired Roman citizenship and their freeborn children, particularly sons.2 Besides celebrating their success in life, the memorials thus also demonstrate their hopes for the future.

Most modern studies focus on freedmen, including freedwomen implicitly or mentioning them only in passing.3 Though freedwomen shared the ambitions and (dis)advantages of their status group, they also differed from their male peers both legally and socially.4 Therefore, it seems worthwhile to look at the funerary monuments of freed slaves from the perspective of freedwomen. What may we infer from the way they were represented on their tombs? Since freedwomen were actively involved in setting up grave monuments for their partners and themselves, they probably had a say in their posthumous representation. (How) did they shake off the stigma of slavery and express their new status as Roman citizens? And what relationship did their epitaphs and portraits show to the normative image of the Roman matrona?5

This article presents an overview of the main patterns of funerary commemoration of freedwomen in Roman Italy from the late first centusry BCE to the late second century CE. Within this period the monuments and inscriptions – most of which cannot be dated precisely – are treated in a roughly synchronic way focusing on three partly overlapping themes: the emulation of freeborn (elite) values, the expression of professional pride and the representation of the deceased in formam deorum (in the guise of deities). Though each of these patterns of commemoration deserves a more in-depth treatment than can be given here, it is especially the co-existence of seemingly contradictory elements within, and between, these three main patterns of commemoration that is the focus of this article. By highlighting the complexity of their (self-)representation I hope to shed new light on the extraordinary position of freedwomen in Roman society.6

Marital ideals and the emulation of freeborn (elite) values

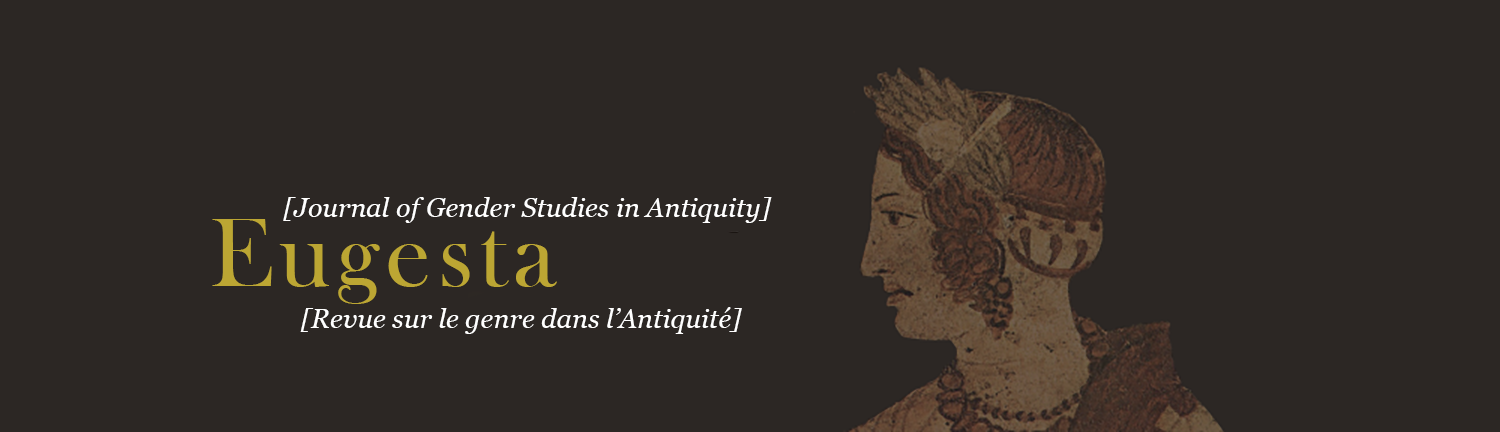

A marble funerary altar in Rome from the late first century CE (fig. 1) shows a man and a woman joining their right hands and looking each other in the eyes. Their heads have been carved as portraits and they wear the public dress of Roman citizens: a toga for the man and a long tunica covered by a palla (mantle) for the woman. The handclasp gesture (dextrarum iunctio) denotes their legal marriage, which may be confirmed by the scroll in his left hand, and symbolizes the harmony between the spouses.7 On a marble plaque that once marked the entrance to their tomb (which is lost), we find the same couple in a different context (fig. 2). The man lies on a couch with his eyes closed and his back resting on cushions. His wife sits beside him with her head slightly bowed, her left hand supporting her chin in a gesture of mourning. A small dog jumping up to her underlines the intimacy of the setting and symbolizes her domesticity and the marital fidelity of the couple.8 If, as it seems, the dextrarum iunctio on the altar refers to their wedding, the relief on the marble plaque shows the husband on his deathbed mourned for by his devoted wife. Thus, the reliefs epitomize the beginning and end of a lawful and harmonious marriage between two respectable Roman citizens.

Two almost identical inscriptions on the altar and the plaque throw a slightly different light on their relationship:

To the departed spirits of Tiberius Claudius Dionysius. Claudia Prepontis made this for her well-deserving patron, for herself, [on the marble plaque alone:] and for their sui and their descendants.9

The inscriptions reveal that Claudia Prepontis commissioned the grave altar and funerary monument for her deceased patronus, her former owner, thus showing herself to be his freedwoman.10 Judging by his name, Tiberius Claudius Dionysius himself was a former slave too, probably of one of the Julio-Claudian emperors.11 The altar was set up by Claudia Prepontis on the occasion of his death. Almost as an afterthought, the words ‘and for herself’ were added in slightly smaller letters at the bottom of the text. There is no reference to their marriage. Their relationship is implied, however, by the inscription on the marble plaque that once adorned the outside of the tomb, indicating who had the right to be buried there. Apart from Tiberius Claudius Dionysius and herself, this includes their sui (immediate family and dependents) and the latter’s descendants.12 We may therefore assume that the inscriptions and reliefs were meant to complement each other in commemorating their married life, unless Claudia Prepontis tried to improve reality by presenting what was in fact a contubernium (de facto marriage) as a legal marriage.13

Unlike the relatively rare marriages between male slaves and their (former) mistresses, a marriage between a master and his female slave was generally accepted and, with the exception of the senatorial class, even facilitated by law.14 An owner wishing to free his female slave for the purpose of marriage (matrimonii causa) was released from the legal requirement of the lex Aelia Sentia that the slave had to be at least thirty years old to qualify for formal manumission.15 Thus, it seems likely that, sometime after his own manumission, Tiberius Claudius Dionysius freed his female slave Prepontis in order to marry her. On their tomb they proudly presented themselves as a legally wedded couple, dressed in the quintessential dress of Roman citizens: the toga and the tunica - palla combination.16 Their formal dress and the affluence that speaks from their large funerary monument show them to have been well-to-do Roman citizens.17

In their representation on the funerary reliefs nothing alludes to their slave background. On the contrary, the handclasp motif, the intimate deathbed scene and the gesture of mourning advertised their marital harmony and adherence to traditional Roman values, thus emulating the ideals of the Roman elite. Emulation of Roman values was important for the public identity of both freedmen and freedwomen. It helped them to overcome the social stigma that attached to their slave background and foreign extraction by focusing on their new dignity as Roman citizens. Since as slaves they had no legal family, officially recognized partners and freeborn children were of the utmost importance for freedmen and duly recorded on their tombs. This held even more for freedwomen. Given the dubious sexual reputation of female slaves, a lawful marriage and adherence to matronal values such as chastity, domesticity and marital fidelity, were vital for their reputation. Their forced sexual availability as slaves created the stereotype of promiscuity – a classic example of ‘blaming the victim’ – that stayed with them after their manumission, as appears from the stereotype of the freedwoman courtesan in Roman poetry.18 Thus, a lawful and respectable marriage was essential for freedwomen to shake off the stigma of immorality.

In the inscription, Claudia Prepontis conspicuously uses the word patronus to denote her patron-husband, who judging by his name was a freedman himself. At first sight, their joint emulation of freeborn elite values seems to contrast with her explicit reference to her former slave status. Possibly, the acknowledgement of her unfree past enhanced their achievement; we should keep in mind that part of the public of the funerary monuments must have been their social peers. In any case, her choice of words suggests that no shame was attached to her freed status nor is there any noticeable tension between her status as a Greek freedwoman and her emulation of Roman elite values.

By marrying her patron, Claudia Prepontis rose in status. A marriage to a former owner who belonged to the elite meant an even greater social ascent. As the wife of a man of elite rank, a freedwoman shared in the prestige and privileges of his class. This rise in status with its successful emulation of Roman values is reflected in funerary portraits of freedwomen that can hardly be distinguished from those of elite families.19 For instance, a large marble grave relief from Rome in the late Republic or early Augustan period (fig. 3) shows the portrait busts of an elderly couple carved in the veristic style typical for elite portraiture of the time. The wrinkles of the male portrait and the lines around his mouth lent him the dignity of age and the thin lips and sober hairstyle of the wife with a topknot (‘nodus’) on her forehead and her hair drawn back into a bun in the neck underline her traditional virtuousness. The veristic busts in high relief set into shells framed by laurel wreaths bring to mind the imagines maiorum, the ancestor portraits in the houses of the elite, and are indeed called imagines.20 The inscription under their portraits, carved in a tabula ansata (tablet with dovetail handles), gives a twist to their elite presentation:

[Left] Lucius Antistius Sarculo, son of Gnaeus, of the voting tribe Horatia, Salian priest at Alba (Longa), also Master of the Salians.

[Right] Antistia Plutia, freedwoman of Lucius.

[Below] The freedmen (Antistius) Rufus and (Antistius) Anthus at their own expense set up the portraits (imagines) for their patron and patroness because of their merits.21

As a master of the ancient college of Salian priests, the freeborn husband was of elite rank. He married his former slave Plutia, who upon manumission acquired his family name and, as his wife, enjoyed the honours of his rank. There is a slight discrepancy between the relief, which presents them as a married couple, and the inscription. The latter refrains from mentioning their marriage, though their relationship is implied by their joint freedmen. We may again assume that relief and inscription were meant to complement each other. Her portrait seems to have been deliberately carved in the style used for elite women of her days. Yet, in agreement with the habits of the time, the inscription records both his filiation and her libertination. Probably, this reflects her pride in her achievement and concomitant rise in status from a Greek slave to a respectable Roman matrona.22

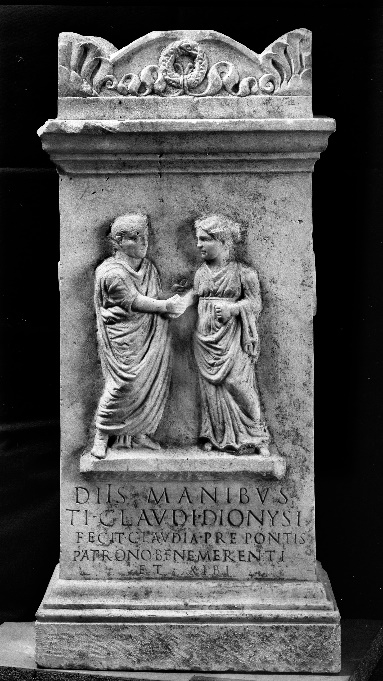

Similarly, the well-known funerary busts in the Vatican museums (fig. 4) portraying an elderly couple in dextrarum iunctio and formally dressed in toga and the tunica – palla combination, so closely resemble portraits of the republican elite that they were popularly known as ‘Cato and Porcia’. However, as can be learned from the inscription that once belonged to it, they represent a Greek freedwoman and her former owner.23 On their expensive funerary monuments these wealthy freedwomen emulated the image and traditional values of women of the Roman elite to the extent that they cannot be distinguished from them. It is only through the inscriptions that we gain a more differentiated view allowing us a glimpse of the complexities of their lives.

For female slaves, marrying their (former) masters provided a way out of slavery and a channel for social mobility that was hardly open to their male counterparts. Yet, a freedwoman marrying her former master was bound more closely to her patron-husband than freeborn women were. Apart from other legal disadvantages, a freed wife was not allowed a divorce against her patron-husband’s wishes and needed his consent to remarry.24 We may expect that a marriage to an often much older master was not necessarily attractive to a young woman. Yet, being a slave, she hardly had a say in the matter and given the choice between slavery and a marriage to her patron most will have consented.25 The funerary monuments highlight the harmony of the marriages between patrons and their freed wives.26 Though the inscriptions reveal the slave background of the wife and the inequality in age and status between the partners, they do not normally shed light on possible conflicts between them.

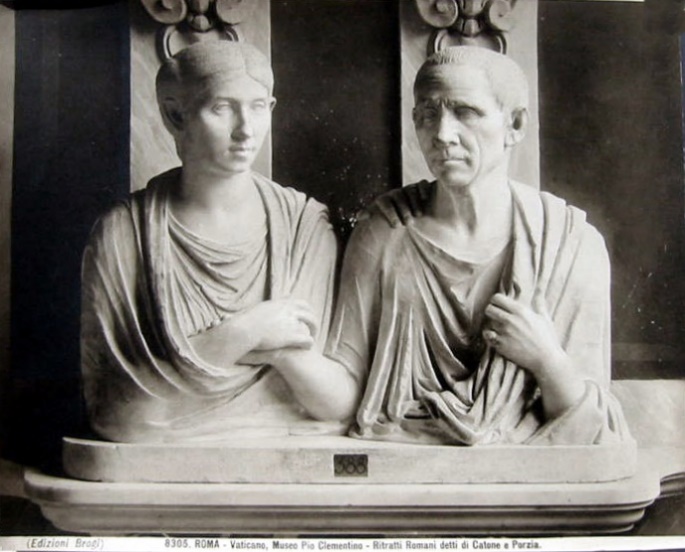

A curse inscription on the back of a richly decorated funerary altar in Rome provides an unusual insight into the emotional conflicts that such (forced) marriages between an elderly master and his former slave might entail. The altar was set up for Junia Procula, a freeborn girl who died at the age of almost nine years old. Her portrait-bust in a medallion adorns the front of the altar (fig. 5). The inscription under the relief records that her father, Marcus Junius Euphrosynus (judging by his name, a freedman), built the tomb not only for his daughter, but also for himself and for his wife and freedwoman, Junia Acte. Remarkably, her name was later erased (fig. 6). The curse on the back of the altar (fig. 7) explains why:

Here are engraved the eternal marks of disgrace of the freedwoman Acte, a treacherous, deceitful, and hard-hearted poisoner. I wish her nail and rope made out of broom, that she may tie around her neck, and glowing hot pitch to burn her evil heart! Though manumitted without payment, she deceived her patron by eloping with an adulterer, and she abducted his servants – a maid-servant and a boy – while he was lying in bed, so that he pined away, a lonely, abandoned, and wrecked old man. And the same marks of disgrace for Hymnus and for those who went off with Zosimus.27

We may reconstruct that Marcus Junius Euphrosynus had freed his female slave, Acte, in order to marry her. To underline her moral debt to him, he adds that he had manumitted her free of charge (gratis), though in fact payment would have been highly unusual in the case of manumission for marriage.28 Since their freeborn daughter, Junia Procula, died at the age of ‘eight years, eleven months and five days’ and was mourned by both parents, we may infer that they lived together as a family for nine years at least.29 Sometime after their daughter’s death, however, the marriage failed and, being unable to initiate a divorce, Junia Acte went off with a lover (adulter) taking two of her husband’s slaves with her and leaving him to waste away in bed as ‘a lonely, abandoned, and wrecked old man’. Possibly, her elderly husband suffered from some ill-understood disease, which he attributes to her malice calling her a ‘treacherous, deceitful, and hard-hearted poisoner’.

In his hope for revenge, the deceived patron-husband curses his wife, wishing her ‘rope and nail’ to hang herself and burning pitch to consume her heart. By inscribing his curse on the back of the funerary altar of their prematurely deceased daughter he appealed to the powers of the underworld to take pity on him and punish his ungrateful and faithless wife.30 In order to deny his wife the right to be buried in his tomb and to wipe out her memory or damage her reputation in the eyes of his peers he erased her name on the front of the altar.31 Thus, the front and the back of the altar speak to different audiences: the inscription on the front is addressed to the passers-by; that on the unworked back, which may have stood against a wall, is meant for the gods alone.

The curse inscription allows us a glimpse of the complexities of the lives of freedwomen marrying their former masters. This is not reflected in their funerary monuments, however, which invariably portray them as devoted wives and respectable Roman citizens. Freedwomen marrying their elite owners experienced an enormous rise in status and, on their funerary portraits, some can hardly be distinguished from women of their new social class. The same holds for the more common marriages between freedwomen and their wealthy freed owners. They were part of a larger group of well-to-do freed people in the early empire, who in their funerary portraits took their inspiration from the public statues of the elite.32 On their tombs, they successfully conformed to the imagery and moral values propagated by the freeborn Roman elite. Despite the possible hardships of their lives as freedwomen, the notion of the leisured and respectable Roman matrona symbolised how they wished to be remembered.

Professional pride and the ideal of domesticity

In early imperial Rome, freedmen dominated the class of craftsmen, merchants and shopkeepers.33 Because of their specialized training as slaves and the (financial) support they received from their wealthy patrons they were often successful in their trade.34 This also held for freedwomen, whom we find in a range of occupations, albeit less frequently than men.35 Despite elite prejudices against work and small businessmen, the class of artisans increasingly derived their status and prestige from their skilled occupation, hard work and commercial success.36 However, judging by the imagery displayed on their tombs, the meaning of work was not the same for (freed) men and women.

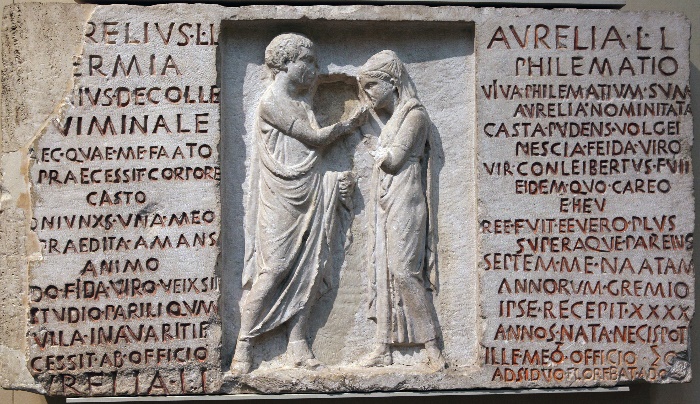

I’ll start again from an example. On a slightly damaged funerary relief from late republican Rome (fig. 8) we see a couple facing each other. They are portrayed in the formal outfit of Roman citizens (the toga for the husband and the tunica and palla for the wife), the handclasp motif symbolizing their lawful marriage and marital harmony. In an affective variation of the dextrarum iunctio the wife holds her husband’s right hand in both her own and raises it to her lips as if for a kiss. This tender gesture probably alludes to her Greek name Philemation, which derives from the word φίλημα, ‘kiss’.37 Their mutual fondness is echoed in the verse inscriptions, in which husband and wife are made to address the passers-by:

[Left] Lucius Aurelius Hermia, freedman of Lucius, butcher at the Viminal Hill. She, who by fate preceded me in death, chaste in body, my one-and-only wife, who fondly took possession of my heart, faithful to her faithful husband she lived with equal affection. She never failed from her duty because of selfishness. Aurelia, freedwoman of Lucius, [here the text breaks off].

[Right] Aurelia Philematio(n), freedwoman of Lucius. Alive, I am called Aurelia Philematium; chaste, modest, unfamiliar with the common crowd, faithful to my husband. My husband, whom I now miss, alas, was my fellow freedman and was in fact and in truth more than a parent to me. When I was seven years old, he took me to his bosom. At the age of forty, I am overcome by death. Because of my unremitting sense of duty, he flourished in all [here the text breaks off].38

As we learn from the incomplete inscriptions – we probably miss the finishing lines of both texts –, the Greek couple had been slaves in the same household and, judging by the word conlibertus (fellow freedman), were manumitted together. Alternatively, Lucius Aurelius Hermia may have bought his fellow slave Philematium after his own manumission and set her free in order to marry her. He must have been much older than his wife and had been her protector from an early age, ‘taking her to his bosom’ when she was seven years old and showing himself ‘more than a parent’ to her. The comparison to a parent refers not only to their difference in age, but also underscores the importance of family to freed people who as slaves had no legal relatives. The expression gremio ipse recepit suggests that their relationship may have had a sexual component from the start, when she was seven years old. For female slaves, this was not unthinkable.39

Though the younger partner, Philematium died before her husband. The monument therefore probably reflects his view of their marriage. Apart from expressing the mutual love and fidelity of the couple, both inscriptions focus on her traditional virtues. Philematium is said to be chaste, modest, true to her husband and ‘unfamiliar with the common crowd’ (volgei nescia), thus embodying the domestic virtues and marital devotion of the exemplary Roman matrona. This is mirrored by her affective gesture and bowed head, which present her as a devoted and submissive wife.40 Like Claudia Prepontis and Tiberius Claudius Dionysius, these Greek ex-slaves are depicted on their tomb as respectable Roman citizens who successfully adopted Roman values and marital ideals. In fact, by their old-fashioned outfit and moral stance they presented themselves as more Roman than the Romans.

Less suited to elite values, however, is the deliberate reference to their work. As recorded in his inscription, Lucius Aurelius Hermia was a butcher at the Viminal Hill in Rome. Though his wife is presented as the model of domesticity, her constant commitment to duty, which is emphasized at the end of both inscriptions, may be connected to her husband’s butcher’s shop. In the inscription at the right, which presents Philematium as speaking, his flourishing business is attributed to ‘my unremitting sense of duty’. Thus, it seems likely that Aurelia Philematium worked together with her husband in the butchery. At first sight, this seems to conflict with the old-fashioned virtues and dress of a Roman matrona, who was expected to lead a life of leisure. On top of that, Philematium is praised for being ‘unfamiliar with the common crowd’. Yet, in many epitaphs of freedwomen of the artisan class domestic virtues are presented as merging happily with hard work and success in business.41

A well-known relief of a butcher’s shop from Rome, now in Dresden (fig. 9), confirms this. The relief from the early second century CE may have been a shop sign or, more likely, part of a funerary monument. It shows a bearded butcher dressed in a short tunic (the workman’s dress) chopping meat with a large cleaver. Pieces of meat, sausages and a pig’s head hang on hooks from a bar above. Facing him, a woman is seated on a high-backed chair with foot stool, which was often used for Roman ladies.42 Her elaborate coiffure and formal dress (long tunica and voluminous palla) present her as a wealthy Roman matrona. However, her writing-tablets, in which she makes notes, suggest differently. This is not a rich customer with a shopping list, but a female bookkeeper or, more likely, the butcher’s wife keeping the accounts. Unfortunately, an identifying inscription is lacking. The difference between the man wearing working clothes and the well-dressed seated matrona might even suggest that she was the owner of the butchery and he her freedman.43 Like Cameria Iarine, who will be discussed below (n. 52), she may have been a freedwoman who freed and married her co-working slave. If so, the relief portrays the freed couple working together in the butchery, her hairstyle and matronly dress suggesting both respectability and affluence and, by implication, their flourishing business.

The representation of these butchers’ wives combines work with traditional female virtues in such a way that they pose as exemplary matronae domisedae (‘housewives’), while at the same time referring to their professional duties. This also holds for several other funerary monuments commemorating female professionals. Text and image complement one another and should, where possible, be ‘read’ together. For instance, an incomplete marble tombstone in Emerita in Hispania Lusitania from the late second century CE reads:

Dedicated to the departed spirits of Sentia Amarantis, aged 45. Sentius Victor commissioned this for his dearest wife, with whom he lived for 17 years.44

In combination with her Greek cognomen, their shared family name suggests that Sentia Amarantis was a freedwoman. The couple must have been fellow-slaves in the same household or Sentius Victor freed his slave Amarantis for the purpose of marriage. At first sight, the text looks like a conventional epitaph of a husband commemorating his ‘dearest wife’. The accompanying relief depicting a woman pouring wine from a large barrel into a jug, however, shows her in her professional role (fig. 10). Sentia Amarantis is dressed in a sleeved tunica, which falls halfway down the calves. Unlike the long tunica and voluminous palla of the Roman matrona, which allow little freedom of movement, this short upgirt tunic was typical for working women.45 We may infer that Sentia Amarantis worked as an innkeeper, perhaps together with her husband, and that her profession was a reason for pride and worthy to be depicted on her tomb.46

Numerous inscriptions on the tombs of freedmen and in the columbaria (communal tombs with niches for urns) of the slave and freed staff of wealthy households advertise their profession as a marker of their social identity.47 Following the habits of their male peers, also some freedwomen recorded their profession on their tombs or were commemorated by others in their professional role. Except for banking and building, freedwomen were involved in a remarkable wide range of occupations. We find them not only in gendered professions, as hairdressers, wet-nurses and midwives, but also as physicians, in commerce and a limited number of crafts (primarily clothing and luxury production), and in entertainment.48 In most occupations women seem to have formed only a tiny minority, however, amounting to a few percent or less.49 Since especially skilled occupations were recorded or work that was particularly appreciated by their former masters, such as that of wet-nurses, the epitaphs do not reflect the actual scope of women’s work in daily life. Unskilled labour and infamous professions, such as prostitution, are not recorded on women’s tombs, not to mention the fact that most people from the working classes did not get an epitaph at all.

Inscriptions, therefore, cannot be used to assess the extent of women’s participation in work and trade, for instance as co-working wives.50 Apart from this, the ideal of the matrona and the habit of using the masculine plural to indicate a mixed-gender group obscure female professionals from our view. Two inscriptions in Rome commemorating a group of purple-dyers and tailors of fine clothing may illustrate this:

Decimus Veturius Diogenes, freedman of Decimus, living; Decimus (Veturius) Nicephor(us), freedman of Decimus, deceased. Veturia Flora, freedwoman of Decimus, commissioned this during her lifetime from her own resources for herself, her patron, her fellow-freedman and her freedman. Nicophor(us), my fellow-freedman, lived with me for 20 years. Purple-dyers in the Marian district. Decimus Veturius Philargyrus, freedman of Decimus and of a woman, living.51

Cameria Iarine, freedwoman of Lucius, made this for Lucius Camerius Thraso, freedman of Lucius, her patron, and for his patron Lucius Camerius Alexander, freedman of Lucius, and for Lucius Camerius Onesimus, her own freedman and husband, and for all their descendants. Tailors of fine clothing on the Vicus Tuscus.52

Here we see two freedwomen, Veturia Flora and Cameria Iarine, commissioning tombs to commemorate themselves, their patrons, their fellow-freedmen and their own freedmen. Veturia Flora lived together with her fellow-freedman Decimus Veturius Nicephorus, and Cameria Iarine had freed her slave Onesimus in order to marry him. Her proud attestation of the fact that he was her libertus et vir shows that within the class of freedpeople this went without censure (cf. n.14 above). The financial capacity of both freedwomen, who built the communal tombs from their own resources and owned (and set free) their own slaves, shows that they occupied an important position in these workshops. Possibly they were shopkeepers working together with their male staff as purple-dyers in the Marian district on the Esquiline and as tailors of fine clothing on the Vicus Tuscus, a fashionable shopping street leading to the Roman forum. The masculine plural purpurarii (purple-dyers) and vestiarii tenuarii (tailors of fine clothing), therefore, includes female workers or managers and the same may hold in other cases.

On the tombs of these freedwomen work is presented as a reason for pride and self-identification. Their professional skills brought them prosperity and respect in the eyes of their peers. Yet, at the same time, working women were often portrayed as leisured matronae for reasons of female propriety. The ambivalence of their representation reflects their desire to reconcile roles that were, in the eyes of the Roman elite, incompatible. Yet, by emphasizing, on the one hand, the respectability and traditional virtues of the Roman matrona and, on the other, the prosperity earned by their hard work and professional skills they combined the best of two worlds. Thus, though overstepping traditional boundaries by their profession, these working women confirmed the norm of female domesticity and presented themselves on their tombs as the respectable Roman matronae they aspired to be.53

In the guise of goddesses

In the late first and second centuries CE we find an unusual form of funerary representation, which combines the portrait head of a wealthy woman, her hair elaborately dressed according to the fashion of her days, with the nude or semi-nude body of the goddess Venus (figs. 11 and 12). This style of commemoration is not widespread: the statues are mainly from Rome and the area around it, and date from the Flavian period to the mid second century CE. Some of these portrait statues were later removed from their original setting in order to be re-used for the adornment of bathhouses and villa’s. Yet, where their context is secure, they can be attributed to the funerary milieu of wealthy and successful freedmen of the emperor, who formed a privileged elite among Roman freedmen.54 This is confirmed by inscriptions and the scarce references in the literary sources discussed below. Therefore, it has been generally accepted that the portrait statues of the mostly quite stern-looking elderly ladies with the body of Venus reflect a fashion among imperial freedmen in Rome and surroundings to commemorate their wives in the guise of deities (especially Venus, Ceres and Fortuna).55 Considering the enormous costs of the sumptuous tombs and the life-size free standing statues, the practice must have been restricted to the wealthiest and most prestigious among imperial freedmen.

Though limited in numbers, the phenomenon of setting up statues in formam deorum, as it is called, is well-studied.56 In order to distinguish it from the public deification of members of the imperial family, by which it was inspired, it has been called ‘private deification’ or ‘private apotheosis’.57 In contrast to the official deification of the empresses, however, imperial freedwomen commemorated in their tombs with statues in the guise of goddesses were not worshipped as deities. Despite Statius’s letter to the imperial freedman Abascantus in the preface to his fifth book of Silvae: ‘For to love a wife during her lifetime is a pleasure, after her death a religio’, there are no indications that the godlike portrait statues of his wife Priscilla (or any other freedwoman) were offered sacrifices or religious rites beyond the conventional tribute to the deceased.58 Therefore, the terms ‘private deification’ and ‘private apotheosis’ are somewhat misleading and will not be used here. I will also refrain from repeating the much-debated controversies about the origin of the habit and the identification of statues in formam deorum, which is beyond the scope of this article. My aim here is to briefly discuss the main examples of women’s funerary commemoration in the guise of deities with an eye to a better understanding of the complexity of the (self-)representation of freedwomen.

Three well-known inscriptions on a large marble epistyle, a marble plaque and a funerary altar decorated with the attributes of Fortuna and Venus from a funerary monument on the Via Appia may be used to exemplify the practice. They record that Claudia Semne, wife of a freedman of the emperor Trajan, was commemorated with a tomb, a lush garden and shrines with portrait statues depicting her in the guise of deities (in formam deorum), namely Venus, Spes and Fortuna.

[On the epistyle] For Claudia Semne, sweetest wife, Marcus Ulpius Crotonensis, freedman of the emperor, set this up.

[On the marble plaque] For Claudia Semne, his wife, and for his son Marcus Ulpius Crotonensis, (Marcus Ulpius) Crotonensis, imperial freedman, made this. To this monument belongs a garden, in which there are arbours, a vineyard, a well and shrines containing statues of Claudia Semne in the guise of deities (in formam deorum). All this was surrounded by me with a wall. This monument will not pass to the heir.

[On the altar] Dedicated to Fortuna, Spes, Venus and to the memory of Claudia Semne.59

Claudia Semne was buried together with her freeborn son, four portraits of whom survive showing him in different costumes. Her own portrait statues in the guise of goddesses are lost, but the pediments of the shrines with the symbols of the deities in question were found.60 As the inscription on the altar makes clear, however, it is dedicated to Fortuna, Spes and Venus, but to the memory of Claudia Semne. Despite the divine associations of her portrait statues, she is not addressed as a goddess herself.61

Some idea of the presentation of Claudia Semne’s statues in the aediculae may be gained from the ornate funerary monument built by the freed couple Quintus Haterius Tychicus and Hateria Helpis in Rome. One of its relief panels depicts the lavish temple tomb for Hateria Helpis, which shows her nude portrait statue in the guise of Venus standing inside the shrine.62 The custom of representing a deceased wife in the guise of goddesses is also reflected in Roman poetry. In his epicedium (funeral poem) on the death of Priscilla, the wife of Titus Flavius Abascantus (freedman and ab epistulis of the emperor Domitian), Statius describes her imposing mausoleum on the Via Appia in which her embalmed body was surrounded by marble and bronze portrait statues depicting her as Ceres, Diana, Maia and Venus.63

How should we understand such portrait statues representing the deceased in the guise of goddesses? Did the naked bodies of statues in the guise of Venus not conflict with Roman ideals of the chaste matrona? When considering the possible meaning of the statues, we should keep in mind that the idealized bodies of these female portrait statues should not be understood as their own. They were modelled on various Greek statue types of Aphrodite/Venus, especially the Capitoline and Knidian Venus. Thus, the women portrayed were not showing their own naked bodies, but – as has been convincingly argued by Larissa Bonfante – wore the nude body of the goddess as if it were a ‘costume’.64 By representing his deceased wife as Venus, the husband associated her beauty, charm and desirability with that of Venus, thus symbolically raising her to a godlike level. In the same vein, portraits of the deceased as Ceres highlighted her fertility, Diana her chastity, and representations as Fortuna and Spes underlined the blessings the wife had provided to her husband, such as prosperity and hope for the continuation of the family. By their association with the deity, the deceased women were presented as sharing that deity’s virtues. Thus, they were raised above the world of the mortals.65

In their desire to present their deceased wives in the guise of goddesses, wealthy imperial freedmen took their inspiration from the public deification of the empresses who, apart from being consecrated after their death, were often associated with Ceres, Venus and other goddesses during their lifetime.66 One example may suffice. A famous cameo in Vienna shows Livia with the corn-ears and poppies of Ceres and the turret crown and tympanum of Cybele, her drapery slipping off her shoulder associating her with Venus. At the same time, the shoulder straps of her stola present her as a Roman matrona and the radiate bust of Augustus in her hand as priestess of the deified Augustus.67

The habit of fashioning portrait statues in formam deorum incited some couples to commission portrait statues for their tombs in the likeness of Venus and Mars.68 Like respectable married freedwomen being commemorated as Venus, this carried no censure despite the adulterous connotations of the myth. As has been argued by Paul Zanker, not all aspects or connotations of a myth or deity were ‘active’ on all occasions. So if a deceased wife was portrayed as Venus, or a couple as Mars and Venus, the aspect of adulterous sexuality was ignored – or ‘de-activated’ – in favour of the divine beauty of the wife, the heroic virtus and military prowess of the husband, and the mutual love and harmony of the married couple.69 Moreover, any erotic connotation of the idealized nude bodies of the deceased was firmly suppressed by their dignified and stern looking portrait heads.

Nevertheless, some doubts remained. In one of his poems from exile, Ovid felt compelled to qualify his praise of Livia’s beauty by stating that she had ‘the body of Venus, but the morals of Juno’.70 Similarly, in his consolatory poem to the imperial freedman Abascantus, Statius explained that his beloved Priscilla was represented in her tomb as an ‘innocent Venus’.71 Such an ‘innocent Venus’ may be seen on the marble grave relief of the imperial freedwoman Ulpia Epigone (fig. 13). The relief portrays her with the body of Venus and the fashionable hairstyle of her days referring to her beauty, desirability and urbanity. Yet, the wool basket at her feet and her pet dog beside her symbolize her domesticity and traditional virtues.72

Not only wives, but also prematurely deceased children might be likened to deities in their tombs. For girls dying before their marriage, the virgin goddess Diana seems an apt choice. The funerary altar of Aelia Procula (fig. 14), daughter of the imperial freedman Publius Aelius Asclepiacus, shows the hunting goddess with quiver and bow and a hunting dog at her feet. One breast is bared like an Amazon and she is flanked by columns as if in a shrine. On the idealized body of the goddess, based on Greek statuary, the portrait head of a young girl identifies the relief as that of Aelia Procula. The inscription reads:

Dedicated to spirits of the departed, to Diana and to the memory of Aelia Procula. Publius Aelius Asclepiacus, freedman of the emperor, and Ulpia Priscilla made this for their sweetest daughter.73

The altar was set up by a freedman of Hadrian and his wife, the freeborn daughter of a freedman of Trajan, and dedicated to the goddess Diana and (like the altar of Claudia Semne) to the memory of their deceased daughter. This ambiguity is echoed by the relief, which shows Aelia Procula, recognisable by her portrait head, represented as a cult statue of Diana in a shrine.74 As in the case of portrait statues of women in the guise of Venus, we may assume that the less desirable connotations of the goddess, i.c. the fierceness and masculine prowess of the huntress Diana, were ignored or ‘de-activated’ by the viewer. What is emphasized by the assimilation with Diana are the chaste virginity and heroic courage of these girls dying before their marriage.75

When gauging the reasons why some imperial freedmen chose to portray their deceased wives and young children in the guise of deities, two sets of interconnected motives come to the fore. First, grief and a desire for consolation. Profound grief over the death of a beloved wife or favoured child may have induced a mourning husband or father to immortalize their loved ones by identifying them with the gods. In principle, this was not restricted to freedmen. During the late Republic, Cicero’s excessive grief over the death of his beloved daughter Tullia incited his – at the time unprecedented – desire to build a temple (fanum) for her to console himself for his loss. His plans to deify her (he speaks of apotheosis) were never realized, but they kept him busy for several months and eventually helped him to accept her death.76

In the imperial period, the expression of deep grief over the death of a spouse reflects the romantic ideal of marriage found in numerous epitaphs and some literary sources.77 In his epicedium, for instance, Statius describes Abascantus’ desperate sorrow at the death of Priscilla. Portrait images and Statius’ own poem were to lend her immortality and thus assuage the grief of her husband. Waging a ‘giant war with Death’ Abascantus rescued his wife from the pyre: in her tomb, her embalmed body was surrounded by statues of herself in the guise of deities.78 On a smaller scale, attributes of deities depicted on tombs or funerary altars and the garlanding of portrait images heroized the deceased, thus alleviating the grief of those who were left behind.79 In short, divine representation of one’s nearest and dearest served as a consolation for the bereaved. For its particular form and symbols, however, freedmen of the emperors took their inspiration from the official deification of the imperial family.80

This brings us to the second pair of interrelated motives: honour and emulation. By honouring their deceased wives and young children with a sumptuous funeral and portraying them in the guise of deities wealthy imperial freedmen followed the imperial model. Emulating the divine ‘costume’ of wives and children of the emperor (but not the emperor himself), they advertised their closeness to the imperial family. Unlike the official deification and public cult of the empresses, however, the divine representation of freedwomen was restricted to the private realm of the tomb. Their primary public, therefore, were their families, members of their household and close friends visiting the tomb for funerals and commemorative rituals. In short, their social peers. Yet, their grand funerary monuments were designed to address, and impress, a wider audience of passers-by. Thus, they publicly honoured the memory of the deceased.

Within the confines of the burial plot, portrait statues of the deceased with the idealized bodies and attributes of goddesses to some extent suggest divinity and cult. They were placed in niches or shrines, thus resembling cult statues, and images of eagles alluded to apotheosis.81 Statius speaks in almost religious terms about Abascantus’ veneration of the memory of his wife, stressing his pietas and religio.82 However, this closeness to the worship of deities is countered by the veristic portrait heads atop of the idealized bodies of the goddesses, emphasizing the restraint and matronly virtues of the deceased. At the same time, their elaborate hairstyle – in the latest fashion – underlined their refinement, urbanity and affluence. Though individualized, these portraits were not necessarily realistic. By advertising the chastity, sobriety and sternness of the deceased, they also idealized the deceased, but then according to Roman moral values.83

The reason why especially imperial freedmen represented their wives in the guise of goddesses may be sought in their ambiguous social status and their proximity to the emperor. Apart from this, Greek statuary and mythological imagery may have had a special appeal for them because of their Greek origins. By presenting themselves as freedmen of the emperor, they advertised their elevated position within their status group. Yet, despite their prominence and their powerful position at the court and in the imperial bureaucracy, freedmen of the emperor suffered from the legal and social drawbacks of their servile past. By emulating the imperial model they may have aspired to heighten their prestige in the eyes of their peers and the general public.

Emulation of the imperial model and representation of the deceased in the guise of deities, however, held the risk of challenging the power of the emperor. By having himself portrayed in the guise of male deities (particularly Jupiter), even if in the private domain of a tomb, a freedman threatened to usurp imperial privilege. It is perhaps for that reason that portrait statues in the guise of deities are found predominantly among their wives and children, the men being more often assimilated to mythological heroes.84 In the words of Barbara Borg: ‘An important factor in the preponderance of women, children and adolescents among portraits in formam deorum will therefore have been the intention to imitate an imperial model, without overstepping the – constantly moving and renegotiated – borderline between aemulatio and blatant hybris.’85

Conclusion

In the period between the last decennia of the Republic and the late second century CE three main patterns may be distinguished in the funerary commemoration of freedwomen. Not all patterns were equally available to all freedwomen due to differences in wealth, training and social position. The representation as wealthy and leisured Roman matronae seems the most enduring form. Imitating the public statuary and ancestor busts of the elite, which were beyond their reach, the portrait images of well-to-do freedwomen advertised their newly gained status as Roman citizens as well as their assimilation to conservative elite values. Their portrayal as respectable Roman matronae helped them to ward off the disrepute of their former servile status, while their expensive funerary monuments proudly reminded the onlookers of their prosperity and success in life. Their posthumous representation, therefore, clashed with the social prejudice freedwomen faced during their lifetime. Though their marriages and matronal status were not legally contested, it was a different matter to be socially accepted as dignified Roman matronae. It is only after death that freedwomen were able to overcome these hardships and ensure their eternal remembrance as the exemplary matronae they aspired to be.

At the same time a smaller, and perhaps less wealthy, group of freedmen identified themselves through work advertising their professional skills in their epitaphs and/or tomb reliefs. Though less numerous than their male peers, many freedwomen participated in trade and manufacture, thus dominating the evidence for working women in Rome. Judging by their epitaphs, they were involved in a broad range of skilled occupations in which they took sufficient pride to have them recorded on their tombs. Due to the gendered ideology of work, however, some of the tombs of freedwomen conveyed mixed messages representing them as leisured matronae while at the same time recording, or alluding to, their profession. Thus, the innovative element of their (self)representation, their identification through work, was anchored in the traditional ideal of the Roman matrona.

During a limited period, from the Flavians to the mid second century, we find a small number of portrait statues of freedwomen using the body types of goddesses. This fashion of immortalizing a beloved wife or child in formam deorum is found mainly among imperial freedmen in Rome and surroundings and was inspired by the public deification of women (and a few children) of the imperial family. By their idealized bodies and partial identification with the goddess, the deceased shared in her main virtues: e.g. fertility in the case of Ceres; beauty, love and charm for Venus; and virginity and courage for Diana. The portrait head, on the other hand, identified the deceased and advertised her traditional virtuousness. In the modern view, body and head may sit uncomfortably together in these statues, but by elevating the deceased to the level of the immortals the bereaved husband or father honoured and worshipped their memory. Thus, they sought consolation for the loss of a beloved wife or the untimely death of a cherished child.

Though restricted to the private realm of the grave, the fashion of portraying the deceased in the guise of deities walked a thin line between emulation and hybris. The magnificent tombs containing shrines with portrait statues of the deceased in formam deorum might be regarded as challenging the cult of the emperors and therefore verging on hybris. This may be the reason why the fashion was largely restricted to the milieu of loyal imperial freedmen, who because of their servile background did not pose a threat to imperial power, and focused on divine associations in the funerary commemoration of their wives and children.

All types of funerary commemoration celebrate the achievement of the deceased who rose from slavery to citizenship and (relative) prosperity. Pride in their success may be the reason why their freed status was so often openly acknowledged in the inscriptions. At the same time, all three patterns of commemoration are aspirational. By advertising their new status as Roman citizens and their assimilation to freeborn (elite) values, prosperous freed families negotiated their status in Roman society, hoping to be accepted as the dignified and loyal citizens they aspired to be and, in fact, were. By leaving behind a lasting memorial they ensured that their memory, as they fashioned it themselves, was preserved for eternity. In doing so, possible tensions between work and the respectable woman of leisure and between the chaste matrona and the nudity of Venus were eliminated. Thus, their funerary monuments broadened the habitual representation of Roman women (the domesticity and mantle statue of the Roman matrona) to include references to work or (nude) portrait statues of identifiable women in the guise of goddesses. For women of the elite the latter was unthinkable, not only for reasons of propriety, but also for fear of challenging the deification of the empresses. Because of their servile past, the representation of freedwomen met with fewer restrictions. As a consequence, their epitaphs and (innovative) funerary images show a greater variety than those of freeborn women. In their tombs, freedwomen broke down the barriers between dignified matronae, skilled professionals and divine heroines.

Figure 1

Funerary altar of Claudia Prepontis and her patron-husband, Tiberius Claudius Dionysius (Vatican Museums inv. 9836).

Photo Arachne archive FA 1778-08_21604.

Figure 2

Funerary relief of Claudia Prepontis and her patron-husband, Tiberius Claudius Dionysius (Vatican Museums inv. 9830).

Photo Arachne archive FA 1778-03_21601.

Figure 3

Marble funerary relief with the portrait busts of Lucius Antistius Sarculo and Antistia Plutia from Rome.

British Museum inv. 2275. Photo Roger B. Ulrich.

Figure 4

The so-called portraits of Cato and Porcia.

Rome, Vatican Museums inv. no. 592.

Figure 5

Funerary altar of Junia Procula.

Firenze, Galleria degli Uffizi, inv. no. 950.

Figure 6

Funerary altar of Junia Procula. Epitaph with erasure.

Firenze, Galleria degli Uffizi, inv. no 950. Photo author.

Figure 7

Curse on the rear side of the funerary altar of Junia Procula.

Firenze, Galleria degli Uffizi, inv. no. 950.

Figure 8

Funerary relief of Aurelius Hermia and Aurelia Philemation from the Via Nomentana in Rome (British Museum inv. 2274).

Photo Roger B. Ulrich.

Figure 9

Marble relief of a butchery (Rome, second century CE). Skulpturensammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, inv. no. ZV 44 (Hm 418).

Photo: Elke Estel, Dresden.

Figure 10

Marble funerary relief of Sentia Amarantis.

Mérida, Museo Nacional de Arte Romano, inv. 676. Photo: Archivo Fotográfico MNAR.

Figure 11

Portrait statue of an unknown woman in the guise of Venus (in the past wrongly identified as Marcia Furnilla, the second wife of Titus).

Copenhagen Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek (IN 0710). Photo author.

Figure 12

Portrait statue of an unknown woman in the guise of Venus.

Rome, Capitoline museums (inv. 245). Photo author.

Figure 13

Funerary relief of Ulpia Epigone (late first century CE).

Rome, Vatican Museums. Photo Arachne Hannestad-71-A0615_21612.

Figure 14

Funerary altar of Aelia Procula (ca. 140 CE). Paris, Louvre MA 1633.

© Musée du Louvre, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Les frères Chuzeville.